Thisblue‑throatedmacawiscritically endangered.

It’sawallofsound.TherearehundredsofchirpingbirdsatUmgeniRiverBirdPark.Listenclosely.Youmighthearablue‑frontedAmazonparrotsingingscales.That’saskillitprobablylearnedfromitsprevious owner.

ManyoftheparrotsinthiszooandbreedingcenterinDurban,SouthAfrica,arerescues.Theyweregivenupbypeoplewhowereunpreparedtotakecareofsuchneedyandlong‑livingbirds.Someparrotscanlivetobe80years old.

Therearemorethan350speciesofparrotsintheworld.Theparrotfamilyincludesparakeets,macaws,cockatiels,andcockatoos.Thedrawtokeepparrotsaspetscanbeirresistible.Theyarehighlysocialandintelligent.Theycanmimichumanvoices.Theyarecapableofcreatingmeaningful,powerfulbondswiththeirowners.It’snowonderthatparrotsareamongthemostpopularpetbirdson Earth.

MajorMitchell's cockatoo

ParrotsatRisk

Parrotsmaybepopular,buttheyfacealotofdangers.Inthewild,deforestationandhabitatlossaremajorthreats.Thegrowinghumanpopulationtakesupspace andresources.Rain forestlands,wheremanylive,areclearedforbuilding materials.

Warmingtrendsintheenvironmentcanalsoresultinhabitatdestruction.Climatecanaffectfoodsources.Itcanalsodisruptbreedingcycles.Pollutionfromacidrainandpesticidescankillparrotsandputfutureparrotsatrisk.Disease,too,isa threat.

Butthereisoneriskevengreaterthanthese.It’spopularity.Unfortunately,thehumandemandforparrotsaspetsseems limitless.

Therearemanysuccessfulparrotbreedingprogramsacrosstheworld.Theyraiseparrotsincaptivitytosellaspets.Despitethis,manyparrotsarestilltakenillegallyfromthe wild.

“IntheUnitedStates,ifyougobuyaparrot,theoddsofitbeingcaptivebredare99 percent,”saysDonaldBrightsmith,azoologistatTexas A&M University.But“ifyou’reinPeru,CostaRica,orMexico,thechancesofitbeingwildcaughtare99 percent.”

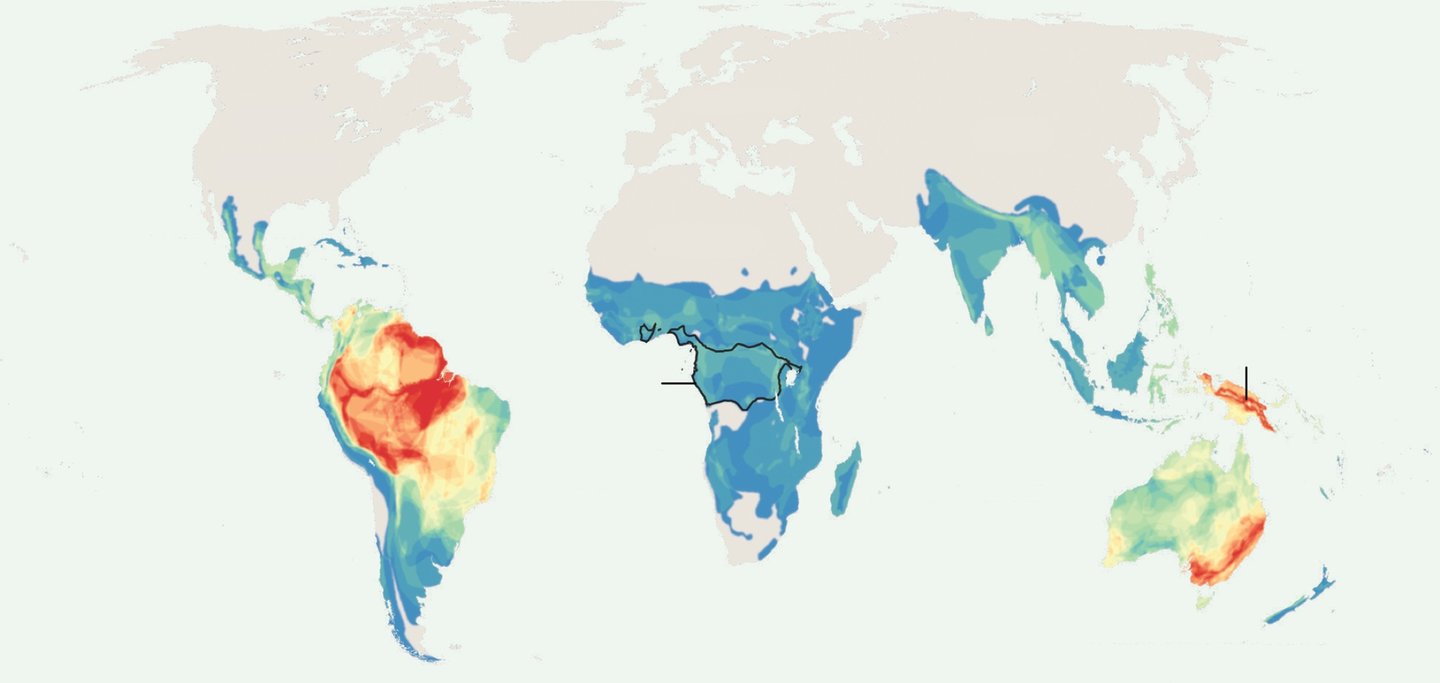

ParrotDiversity

Parrotspeciesliveinrangesonfivecontinents.TheAmazon,NewGuinea,andAustraliahavethegreatest variety.

North America

South America

Africa

Europe

Asia

Australia

Amazon Basin

New Guinea

African gray parrot range

numberofparrot species

fewer

more

DIDYOUKNOW:

Palmcockatoosonlylayoneeggeverytwoyearsandhaveoneofthelowestbreedingsuccess rates.

ParrotPopularity

Onereasonwildparrotsendupaspetsistheillegalwildlifetrade.Thesameorganized‑crimegroupsthathavemadebillionsofdollarstraffickinganimalpartssuchaselephanttusksandrhinohornshaveaddedparrotstotheirlist.Forexample,asingleAustralianpalmcockatoohasbeenknowntofetchupto $30,000 ontheblack market.

Currently,allbutthreeofthe350parrotspeciesqualifyforprotectionundertheConventiononInternationalTradeinEndangeredSpecies,orCITES.CITESismadeupof179nations—allwiththesamegoaloffightingtheillegalwildlife trade.

TheillegalparrottradeisatitsworstinLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean.Herethelawsagainstitarenotalwaysstrictorcanbedifficultto enforce.

However,themostcovetedspeciescomesfromAfrica—theAfricangray.It’sthebesttalkerofthemall.Overthepastfourdecades,atleast1.3milliongrayshavebeenexportedlegallyfromthe18 countrieswheretheylive,accordingtoCITES.Yethundredsofthousandsmorehavelikelydiedintransitorbeentakenillegallyfromtherain forestsofWestandCentral Africa.

Africangray parrots

ThecenterofthistradeisSouthAfrica.ItexportsmoreAfricangraysthananyothercountry.Historically,mostorderscamefromtheUnitedStatesandEurope.However,lawsbanningthebirdtradeclosedthosemarkets.TheMiddleEastnowfillsthevoid.SouthAfricaexportedthousandsofgraystothatregionin 2016.

Thatyear,CITESmadeacontroversialdecision.ItaddedtheAfricangraytoaspeciallistofotheranimalsthreatenedwithextinction.Tocontinuesellingbirdsabroad,breedersmustnowprovetoCITESinspectorsthattheirAfricangraysareraisedincaptivity,notcaughtinthe wild.