IgrewupinCanadaandintheUnitedStates.Ialwayswasinterestedinlanguages.InthecommunitieswhereIlived,manylanguageswerespokenallthetime.Ilovelanguagessomuch,Ibecamealinguisticanthropologist.That’sapersonwhostudieslanguagesfromaroundtheworld.I’minterestedinhowlanguagesareusedandhowtheychange.AndIlovehowtheyconnectustothepeoplearound us.

OnedaywhenIwasincollege,Ihadacrazyidea.Wouldn’titbeinterestingtodiscoveranewlanguage?Iknow.Itsoundscrazy.Yet,it’s possible.

Languagesdon’tstaythesame.Overtime,theychange.Sometimesanewversioniscreatedthatisnotlikeanythingthathaseverbeenspokenbefore.Tofindit,youhavetobeattherightplaceattherighttime.IhadanideawhereImightlook:Peru,inSouth America.

InPuno,aregionofPeru,peoplespeaktwoindigenouslanguages.Thatmeansalanguagethatisnativetoaspecificplace.Puno’slanguagesareQuechuaand Aymara.

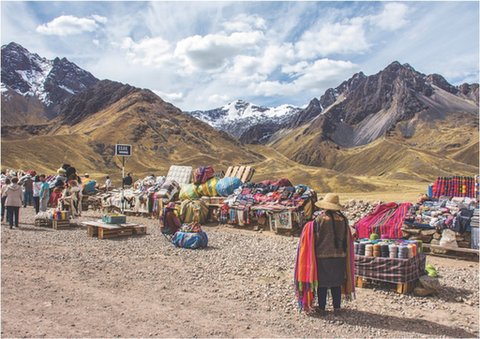

Youheartheselanguagesinthemarketandatcelebrations.ButIwonderedif,overtime,QuechuaandAymaramighthavemeldedtobecomesomething new.

Learn a little Quechua or Aymara.Try these useful words and phrases:

Quechua:

Imanaylla kashanki?

(i-ma-naa-ya ka-shan-kee)

Aymara:

Kamisaraki

(ka-mee-sa-ra-kee)

English:

Howare you?

PunooverlooksLakeTiticaca,thelargest,deepestlakeinthe Andes.

LivingtheHighLife

Totestmytheory,Ipackedmybackpackwithnotebooksandmybestaudiorecorderand microphone.

InthesouthernmostpartofthePeruvianAndesistheAltiplano.InSpanish,thismeans“highandflat.”It’sahigh,dryplateauwithsnow‑cappedmountains.ItishometoLakeTiticaca,thehighestlakeinthe world.

ThecommunitiesinPunoaremorethan3,800meters(approximately2.5miles)abovesealevel.It’ssohighyoucanfeeltheeffectsonyour body.

coca tea

Aymara:

Walikiwa

(wa-li-kee-wa)

Quechua:

Allinmi

(al-yeen-mee)

English:

Iam good.

WhenIfirstarrived,Icouldfeelmyselfbreathingfasterandfeelingdizzy.Later,Ifeltnauseousandhadaheadache.Thiswassorrocha,oraltitudesickness.Thelocalremedywascoca tea.Idranktheteaintheeveningsandsoonfelt better.

Beinghighintheskyalsomeanslessozone.Thisgasintheairprotectsyoufromthesun’sultravioletrays.IntheAltiplano,peoplenevergooutwithouttheirsun hats.

Mountainsloominthedistanceofthisroadside market.

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

BRAZIL

CHILE

PERU

Lima

Puno

region

Puno

Lake

Titicaca

PACIFIC

OCEAN

BOLIVIA