ToProtectandPreserve

Toprotectandpreservesuchvaluableitemsisabigresponsibility.Curatorsunderstandtheriskstoitems,suchastheflagfromthepresidentialbox.Ultravioletlightcanfadeitsdarkbluedyedsilk.Itsfiberscanbreak down.

flag

That’swhycuratorspreservetheflagunderspecialglassthatblocksultravioletlight.Framingtheflagalsoensuresthatitwillbekeptflat.Foldingtheflagcouldcreatelastingcreases.Historicfabricsareoftenrolleduptopreventsuch damage.

Otherdangerscomefromtheenvironment.Dirt,dust,bodyoils,andotherpollutantscanharmobjects.That’swhycuratorsusewhitecottonglovestohandleanyartifact.Curatorsalsohavetoworryaboutpests.Rodentsorbugsmightnibbleonartifacts.Theymightevenusethemtobuild nests.

Changesintemperatureandhumiditycanalsocausedamagelikeshrinkage,mold,mildew,orrust.So,allartifactsarekeptinaclimate‑controlledenvironment.Thecenteralsohasanadvancedfireprotection system.

NationalParkServicemuseumcuratorKamalA. McClarinwearscottongloveswhenhehandlesartifactsliketheflagfromthepresident's box.

tear

ThePathtoPreservation

Insomecases,artifactscomeintoamuseum’scollectionquickly.Inothercases,manyyearscan pass.

AfterPresidentLincolnhadbeenshot,hewascarriedacrossthestreettothehomeofWilliamandAnnaPetersen.There,hewaslaidacrossatinybedinoneofthebackbedrooms.ItwastheroomofayoungarmyclerknamedWillie Clark.

Soldierswerepostedatthedoorsofthehousewhiledoctorsattendedtothewoundedpresident.At7:22a.m.onApril15,AbrahamLincolndiedfromhiswound.WhenClarkreturnedthenextmorning,hisroomwasinshambles,andthepresidentwas gone.

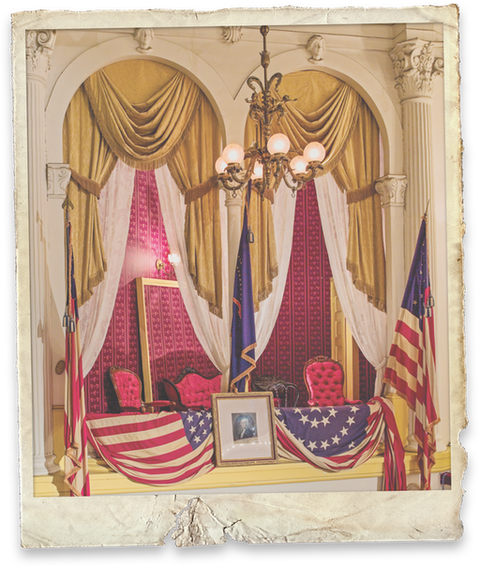

bedroomatPetersonHouse,

locatedacrossthestreetfromFord’s Theatre

WillieClark'slettertohissisterhasbeencarefully preserved.

Fourdayslater,Clarkwrotealettertohissister,Ida.Hewrote:“Sincethedeathofourpresidenthundredsdailycallatthehousetogainadmissionintomyroom….Everybodyhasagreatdesiretoobtainsomemementofrommyroomsothatwhoevercomesinhastobecloselywatchedforfearthattheywillsteal something.”

Clarkhimselfsenthissistersomethingofgreatvalue.Hewrote:“EnclosedyouwillfindapieceoflacethatMrs.Lincolnworeonherheadduringtheevening. . . Itisworthkeepingforitshistorical value.”

Thelacedisappeared,buttheletterremained.Morethan100yearslater,itwasgiventotheFord’sTheatre Museum.

AbrahamLincolnworethiscoat,vest,andtrousersashisofficesuitwhilehewas president.

ThisexhibitshowsthecoatAbrahamLincolnworethenighthewas shot.

Clark’sletterisafirst‑handaccountofwhathappenedrightaftertheassassination.Itiswhatisknownasaprimarysource.Aprimarysourceisanartifact,document,diary,recording,oranyothersourceofinformationthatwascreatedatthetimeunder study.JohnWilkesBooth’sdiaryisalsoaprimarysource.Itis,infact,theonlysourcethatrecordsBooth’s thoughts.

TheFord’sTheatrecollectionisfullofinterestingartifacts.YoucanseetheclothesLincolnworetothetheaterthatnightandmanyother objects.

Thesepiecesofourpasthavebeenpreservedandprotectedsothatpeoplecanseeandconnectwiththem today.

TofindoutmoreabouttheartifactsatFord’sTheatre,goto www.fords.org

TolearnmoreabouttheNationalParkService’sMuseumResourcesCenter,goto www.nps.gov/orgs/1802/

MyCareer

WhennothandlingartifactswithhiswhiteglovesattheMuseumResourcesCenter,KamalMcClarincanbefoundatdifferenthistoricsitesintheWashington,D.C.,area.McClarinservesasaninterpretiverangerwiththeNationalPark Service.

It'shisjobtohelpvisitorsmakeapersonalconnectionwithhistoricplacesandpeople.He'softenworkingatthehomeofFrederickDouglass.Douglasswasaformerslavewhobecameanabolitionist.HepressedPresidentLincolnforequalityforallpeople.McClaringivesvisitorsasenseofhowDouglasslivedand worked.