flowersinGeorgeWashington's garden

It’sabeautifulsummerday,andI’mstandinginthemiddleofGeorgeWashington’sgarden.Idon’tthinkhe’dmind.He’sbeendeadformorethan220 years.Thebiggernewsisthatthegardenontheestateofourfirstpresidentisstillhereandblooming.I’mnottheonlyvisitor.MountVernon,locatedabout

28kilometers(18miles)outsideofWashington,D.C.,isvisitedbyaboutamillionpeopleevery year.

Theplants,flowers,bushes,andtreesthatareinthegardentodayaresimilartothosethatWashingtonplantedwhenhelivedhere.Ateamofresearchersandarchaeologistsworkedhardtorecreatethegardenasitwasin1787.Itwasnoeasytask.Howdidtheyknowwhatto plant?

Historianslearnaboutthepastbystudyingprimarysources.That’ssomethingthatwascreatedatthetimeunderstudy.Oftenhistoriansturntoartifactslikeletters,diaries,manuscripts,maps,oritemslikeclothingorjewelry.But,didyouknowthatnaturecanalsobeusedasaprimary source?

TheGeneral’sGarden

Writtendocumentstellusalotaboutthepast,butnoteverything.Theycanonlytelluswhatthewriterthoughtwasimportantenoughtorecord.Haveyoueverkeptadiary?Whatsortsofthingsdidyouwritedown?Whatdidyouleaveout?I’mguessingyourdiaryonlytoldapieceofyour story.

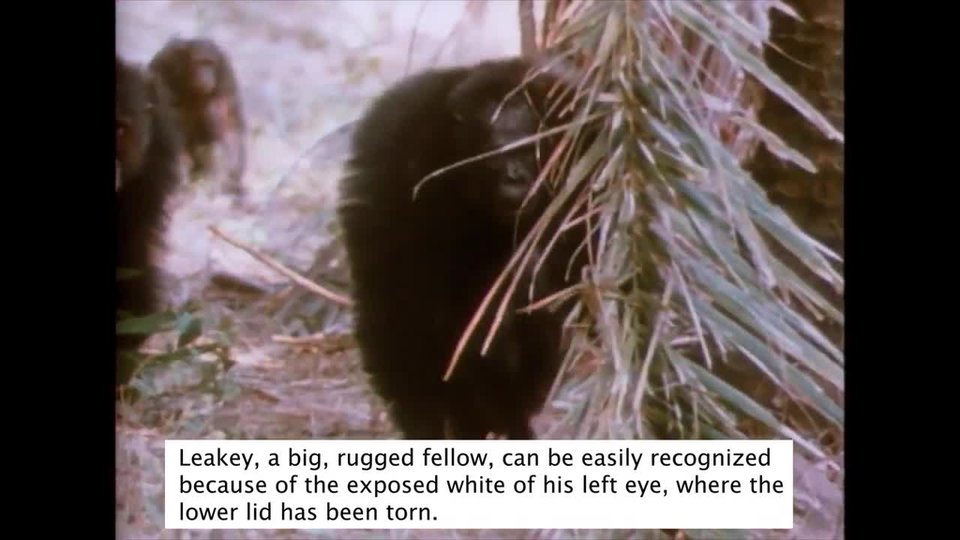

InthecaseofMountVernon,historiansdidhavealotofwrittenrecords.Washingtonkeptnotesonwhatwasbeingplantedbackhome,evenwhenhewasageneralfightingintheRevolutionaryWar.Weknowthattherewerefourmaingardensonthe grounds.

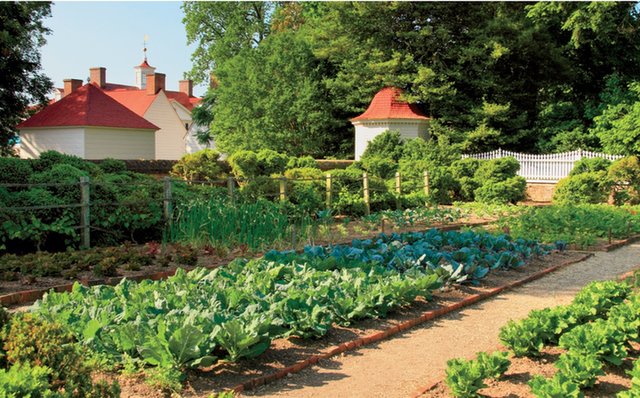

Atthecenterofeachuppergardenplantingbed,Washingtoninstalledrowsof vegetables.

Theseuppergardenboxwoodsweresculptedintofancy shapes.

Theuppergardenwasfilledwithflowers,bushes,andexotictreesthatwereplantedinpatterns.Ithadfruitsandvegetableshiddeninthecenter.ThisformalgardenprovidedabeautifulspaceforWashingtontoenjoyandentertain guests.

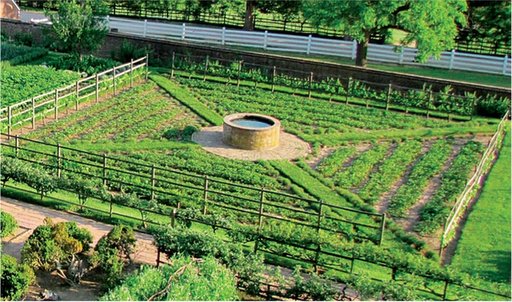

RunningsolargeanestatemeantthatWashingtonhadalotofmouthstofeed.So,hehadalargegardenjustforfood,too.Fruitsandvegetablesgrewinplentyinthelower garden.

Washingtonusedhissmallbotanicgardenasalaboratory.It’swherehetesteddifferentplantstoseeiftheycouldthriveinVirginia'ssoil.Friendsandadmirerswouldsendhimseeds,bulbs,andcuttingsfromallovertheworldto test.

Lastly,Washington’sfailedattemptatavineyardturnedintoafruitgardenandnursery.Grapesdidnotthrivethere,butotherfruits did.

ThelowergardenwasusedtogrowmostofthefoodforMount Vernon.

UPPER

GARDEN

BOTANIC

GARDEN

LOWER

GARDEN

FRUITGARDENAND NURSERY

mapofMount Vernon

TendingtheGarden

Washingtondidnottendtothesegardensallbyhimself.About90enslavedpeopletendedthelandforhim.Althoughmostenslavedpeoplewereilliterate,Washington’sgardenerscouldreadandwrite.Theykeptdetailedlistsandmadedrawingsofwhatwasplanted,when,and where.

Washingtoncloselysupervisedtheselists.Buthistoriansturnedtoothersourcesofinformationtoverifythewrittenrecords.Theylookedatthesoil itself.

ScientistsatMountVernoncananalyzesoiltolearnaboutitsfertility.ThiscanrevealcluesaboutWashington’sfarmingtechniques.ItcanalsoindicatewhyWashingtongrewcertainkindsofcropsatMount Vernon.

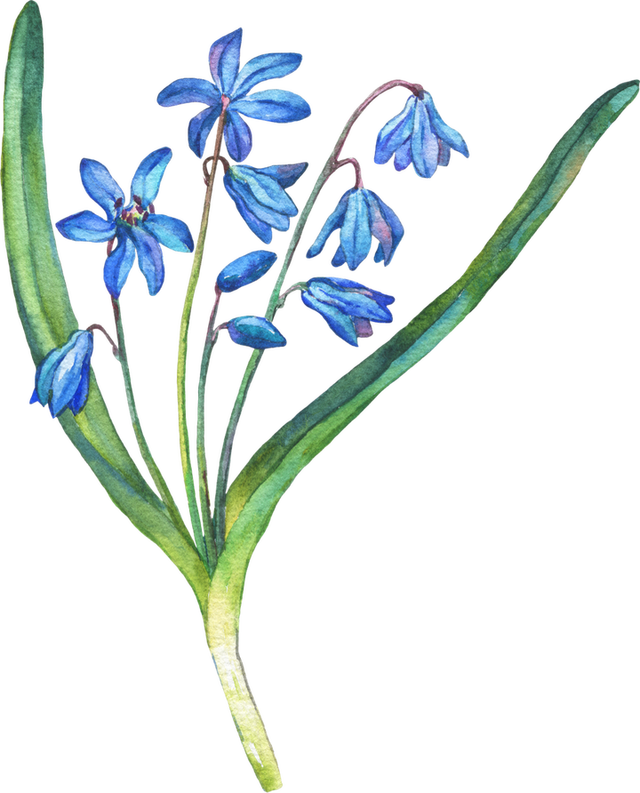

adrawingofalpinesquill wildflowers

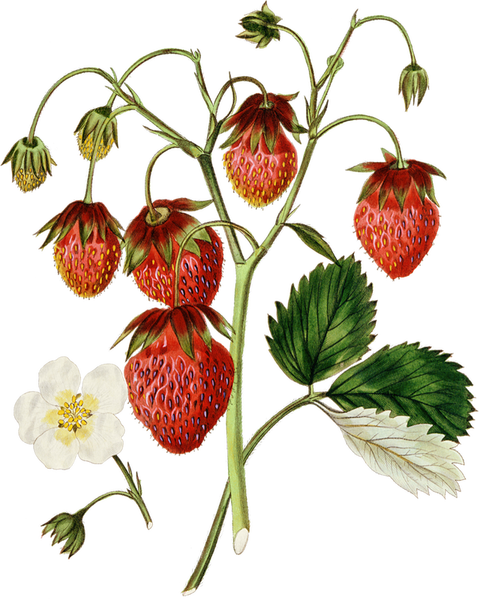

Inaletterfrom1798,afriendsentWashingtonafewscarletalpinestrawberry seeds.

JasonBoroughs,MountVernon’shistoricarchaeologist,hasspentalotoftimedigginginthedirt.MountVernon’steamofarchaeologistsandresearchersspentfiveyearsinWashington’supper garden.

Theteamworked,surveying,excavating,andanalyzingthegardentomakeitashistoricallyaccurateaspossible.TheystartedwithaseriesofplansdrawnbyamannamedSamuelVaughan.VaughanwasanEnglishmerchantwhovisitedMountVernonin1787.TheyconsultedVaughan’splansthenlookedatthegardenitself.Ithadbeenregrownin1985,buttheycouldseethatwhathadbeenplantedwasn’thistorically accurate.