SoleBrothers

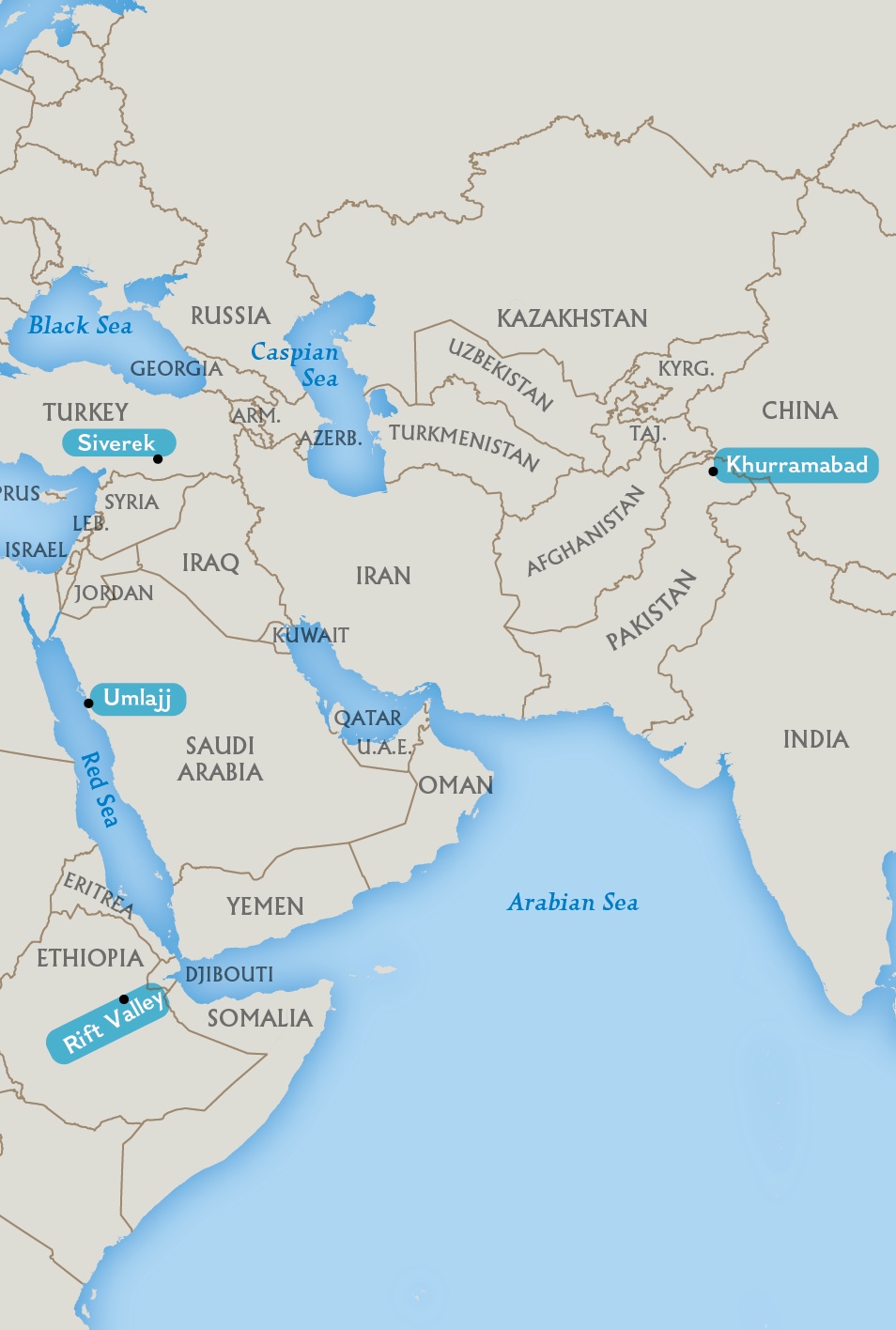

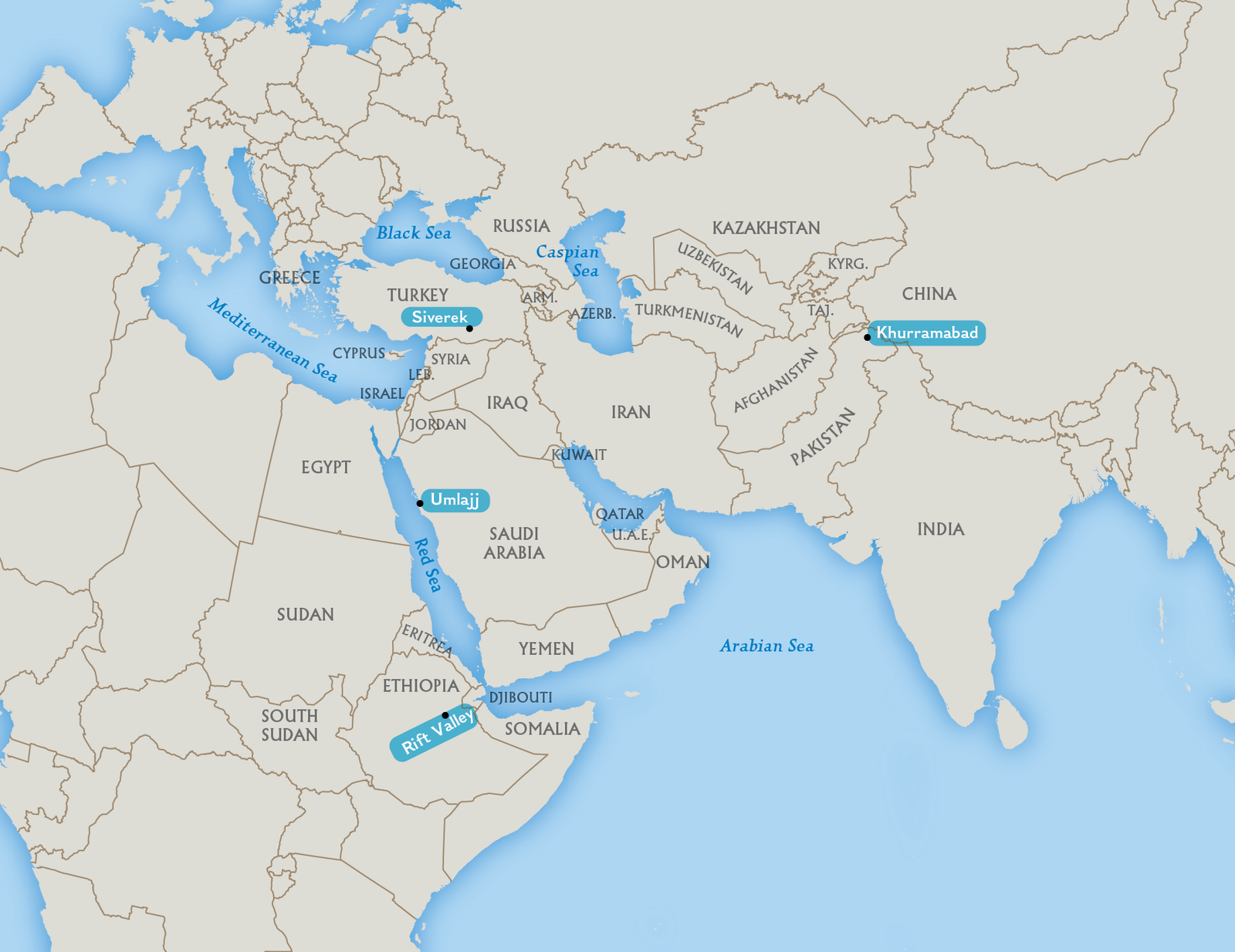

RiftValley,Ethiopia

January31,2013

Salopek’stripwilltakemillionsofsteps,sohisfootwearisprettyimportant.InEthiopia,therearefewshoeoptions.

Howdoyoujudgeaman?Lookathisshoes.Shoesrevealtheirwearer’sclass,style,evenjob.Itisodd,then,tobewalkingthroughaplacewheremillionsofpeoplewearthesame-stylefootweareveryday—thecheap,plasticsandalofEthiopia.Manypeoplebuyandwearthembecausetheyareaffordable.

Acoupleofmycamelhandlersonthispartofmyjourneyworelime-greenplasticsandals.ThesurfaceoftheRiftValleyiscoveredinfootprintsstampedbytheseplasticshoes.YetifEthiopia’ssandalsaremass-produced,theirwearersarenot.Theirtrackstelldifferentstoriesandidentifydifferent people.

ManyEthiopianswearthesamestyleofshoe,madefrom plastic.

Ourguidekneltdowntheotherdayonthetrail.Pointingtoasinglesandaltrack,hesaid,“La’adHoweniwillbewaitingforusinDalifagi.”He was.

Awad’sRefrigerator

Umlajj,SaudiArabia

October30,2013

Salopekandhisguidesmustcarryeverythingtheyneedastheytravelforweeksatatime.Carryingwateracrossthedesertisessential.Butwhosaidanythingaboutitbeingcold?

ThefirstmodernHomosapiens,orpeople,walkedoutofAfrica.Atthattime,theregion’s seaswerelower.Itshillsweregreener.Whatthepeopleexperienced,wedonotknow.Whatiscertainwastheirneedtocarrywater.

Waterisheavy.Tocarryenoughwateracrossgreatdistancesrequiresstrength.Whatdidthefirsthumansuseascontainers?Nobodyknows.Canteensorbucketsmadeofnaturalmaterials?Agurba,orgoatskinwater bladder?

AwadOmran,mycamelhandler,hasasolutiontoquenchingour thirst.

Awad’scold-watercanteenismadefromasack,cardboard,plastictwine,andaplasticwater bottle.

Awadbuildsawater-coolingthermos.It’smadefromjunkdiscardedaroundafarm.Hewrapsalargewaterbottlewithcardboard.Hewrapsburlaparoundthecardboard.Hemakesalonghandlefrom twine.

Awad’sthermosoperatesontheprincipleofevaporation.Wettedandhungonasaddle,itsdampenedcardboardcoolsourdrinkingwater.

Mule-ology

NearSiverek,Turkey

December11,2014

Salopekrarelytravelsalone.He’susuallyjoinedbyaguideandpackanimalsthatcarrysupplies.Here,hewritesabouthismulewhiletravelingthroughTurkey.

Firstthingsfirst:Amuleisnotadonkey.Adonkeyisasmall,long-earedcreaturefromwhichmulesarebredwhenmatedwithahorse.AmuleisananimalIrelyonduringmytravels.Amuleisbigger.Malesarejack mules.Femalesarejennyormollymules.Mulesareusedforallsortsofjobs.Therearecottonmules,sugarmules,miningmules,andmore.

Itdoesn’tmatterwhatyoucallamule,however.Mulesdon’tanswertonames.Eachofmywalkingpartnershascalledourwhitejennybyadifferentname.OneguidecalledherBarbaraforreasonsonlyhecanexplain.AnotherdubbedherSunshine.StillanothercalledherSweetie.JohnStanmeyer,myphotographer,referstoheras Snowflake.

MypreferenceisKirkatir,aTurkishnamemeaning“greymule.”Thetruthisthat,likeallmules,sheanswerstonolabelhandedoutbyhumans.Shecomeswhenshefeelslikeit.Andshedoeswhatshepleases.Thankfully,thatincludescarryingoursupplies!

PaulSalopek’smuleinTurkeymaynotcomewhencalled,butsheshouldersmuchoftheburdenonthewalk.

WalkingGrass

NearKhurramabad, Pakistan

January02,2018

Alonghistravels,Salopekmeetsmanypeoplegoingabouttheirdailylives.Here,inPakistan,hecomesacrosssomefarmersharvestingandcarryinghay.

ThemountainrangethatcutsnorthernAfghanistanfromPakistanisacolddesert.Thereislittlerain.Foralltheirthickglaciersandsnow,themountainsaremostlydry.Inlatesummer,glacialmeltstreamsdown,washingawayatvillages,roads,andtopsoil.

Thepeoplewholivehere,manyofthemfarmerswaitforthepasturestodry.Thentheyharvestwildhay.

AmongthefarmersareRehman AliandBibiPari.They areoldernow.Theirsonshavemovedtobigcities.Buttheyremaintoharvesttheirrockyfieldsthemselves.

IcanbarelyhelpParicarryherload.Yet,toher,itseemslikenothing.Shesays,“Thankyou,brothers,”forthesimpleactofwatchingherwork.

Afarmercarrieshaytohishouseabout3.2kilometers(twomiles)away.