FindingSomethingNew

Cabrastakesgreatcarewhenshethinksshe’sfoundsomethingnew.Shesignalstoherteammatestostopmoving.Shedoesn’twantanysuddenmovementstoscareoffabeetle.Thenshetriestotakeaphotographofthescene.“Iusuallytakephotosoftheirfoodplantandhabitat,”shesays.Thisgivesinformationtotaxonomistsaswellasecologistsand conservationists.

Whenthebeetlesfeelvibrationsontreeleaves,theyfalltotheground.Theyareveryhardtofindindead leaves.

teammatesworkingina forest

Manyjewelweevils,forexample,haverangesastinyasonepatchofforest.Theyeatonlycertainplants.Itisvital,then,toconservetheplantifyouhopetoconservethe beetle.

AFullerPicture

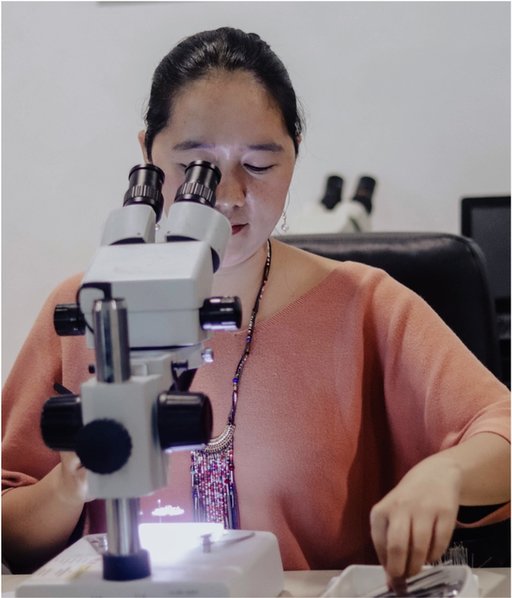

There’sanotherreasonwhyCabrastriestorecordthescene:“Forsomeofmycolleagues,thisisthefirsttimetheyareseeingthespeciesalive,”shesays.Ifpossible,Cabrascollectsabeetleasasample.Thenitcanbelookedatinthe lab.

ThisbeetlewouldbecomeimportanttoCabras’research.Shediscoveredanewspeciesthatlooked similar.

Cabrasusesamicroscopetolookcloselyat beetles.

Thisworkrequiresspecialskills.“Youhavetotrainyoureyestolookintothemicroscope.Butyoualsohavetotrainyourhands,”Cabrassays.Beetlesmustbecutaparttoseewhatisinsidethem.Thatmeansgoodeyesandsteadyhands.But,Cabrascan’talwaystrustwhatshe sees.

WeevilWonders

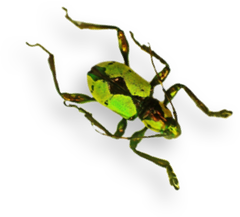

Jewelweevils,forexample,sparklelikegems.Theirelytra,orwingcovers,shimmerwithcolorsfromturquoiseandgoldtoorangeandpink.Thismakesthemeasytargetsforpredators.Butweevilswanttobeseen.Colorisawarning:Don’teatme.Itaste bad.

Thisiscalledaposematism.Theanimalletsitspredatorknowthatitisnotwortheating.Brightcolors,sounds,andodorscanwarnpredators.Cabrasdidn’trealizehowmuchthiswasgoingtoaffecther research.

Thisleafbeetlelookslikesomejewel weevils.