ThestoryofJaneGoodallislikeacampfiretale.Itgetsbetterwitheachtelling.Herstoryisinstantlyrecognizedfromthemanytimesandwaysit’sbeentold.In1965,shewasayoung,untestedscientistwhowantedtolearnaboutchimpanzees.Shehadnoformalbackgroundinresearch.Shewasawomaninthemale‑dominatedworldsofscienceandmedia.Shehadherworkcutoutforher.However,shebecameaworld‑famousfaceoftheconservationmovement.Thisisher story.

GrowingUp

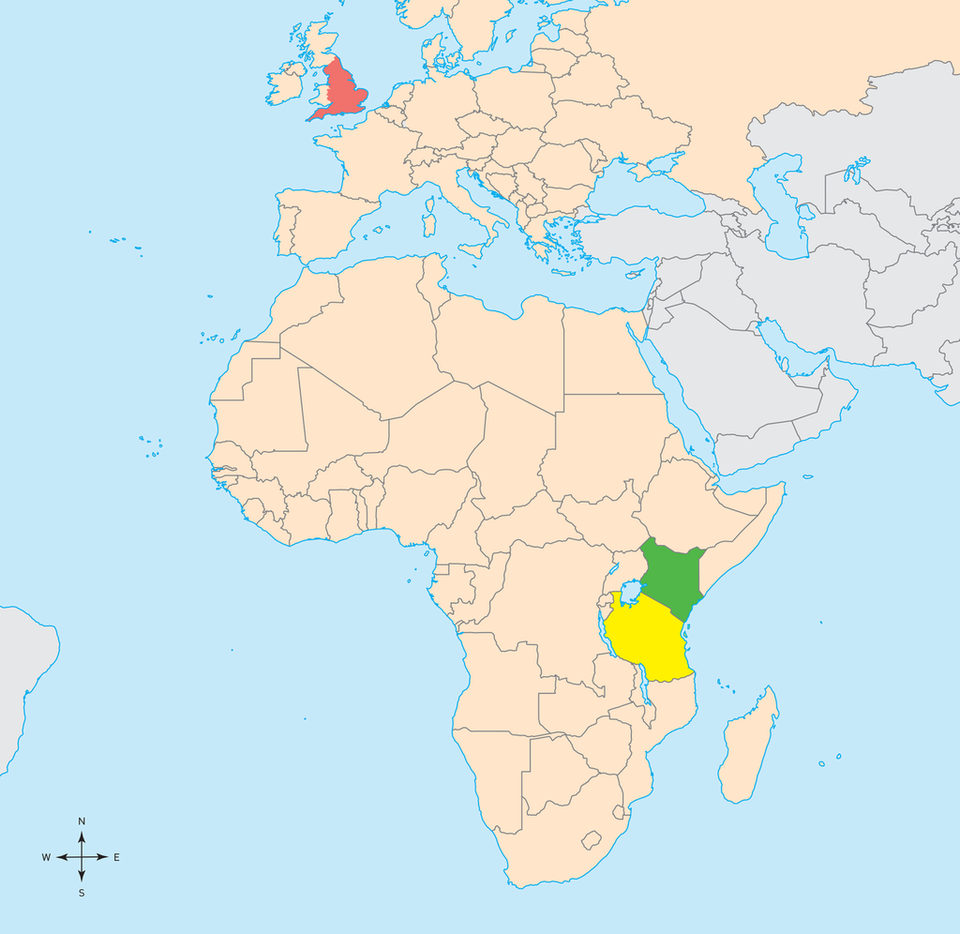

ValerieJaneMorris‑GoodallgrewupinEngland.Fromanearlyage,shewasfascinatedbyanimals.ShedreamedoflivinginAfrica.Herfamilycouldn’taffordtosendhertocollege.So,Goodallwenttoschooltobecomeasecretary.Aftergraduating,shereturnedhome.ShefoundajobasawaitressandstartedsavinghermoneyforanoceanpassagetoKenya.Whenshehadsavedenough,shewenttoAfricatofulfillherlife‑long dream.

OnceinKenya,sheboldlyaskedforameetingwithpaleoanthropologistLouisS. B.Leakey.Hisinterestingreatapesledhimtopioneeringresearchontheoriginsofhumans.LeakeyhiredGoodallonthespotasasecretary.Hesawinherthemakingsofascientist.Later,hearrangedforhertostudyprimateswhileheraisedfundssoshecouldresearchchimpanzeesin Tanzania.

RoughingIt

Bythesummerof1960,GoodallwassettingupcampintheGombeStreamReserveneartheshoresofLakeTanganyika.Shehadenoughfundingforsix monthsof fieldwork.

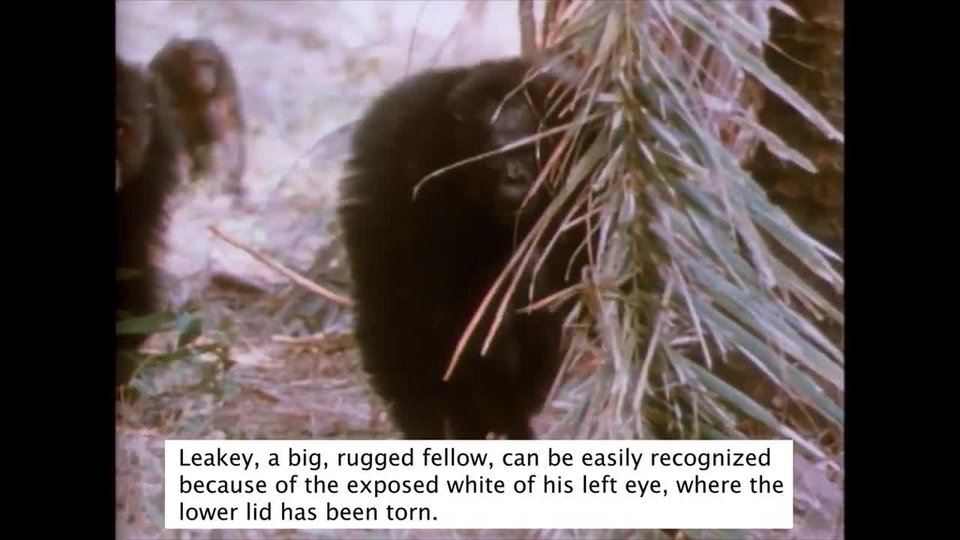

Fromthestart,Goodallfollowedherinstinctsforherresearch.Theestablishedscientificpracticewastousenumberstoidentifyanimalsunder study.Instead,Goodallrecordedobservationsofthechimpsbynamesshemadeup:Fifi,Flo,Mr. McGregor,DavidGreybeard.Shewroteaboutthechimpsasindividualswithdistincttraitsand personalities.

Forexample,whenafemaleshecalledMrs.Maggswaspreparingatreetopnestforthenight,Goodallwrotethatthechimphad“testedthebranchesexactlythewayapersonteststhespringsofahotel bed.”

Goodallspentmostwakinghoursobservingtheanimals.Atfirst,itwasfromafar,throughbinoculars.Overtime,shemovedcloserastheygotusedtoher.Butwithonemonthleftinherstudy,shehadn’tmadeanybig discoveries.

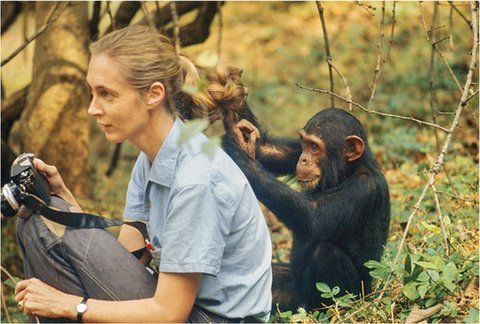

FlinttakesapeekatGoodallfromthetopofher tent.

DavidGreybeardvisitsGoodall’s camp.

TurningPoint

Theneverythingchanged.GoodallmadethreediscoveriesthatwouldnotonlymakeLeakeyproudbutwouldalsoturnestablishedscienceonits head.

Inherfirstdiscovery,sheobservedachimpeatingadeadanimal.Untilthen,scientiststhoughtthatapesdidn’teatmeat.ShehadnamedthischimpDavidGreybeardbecauseofthegreyhaironhischin.HewouldopenthedoorforhertothehiddenworldofGombe’s chimpanzees.

Withintwoweeks,GoodallobservedDavidGreybeardagain.Thistimewhatshewitnessedwastrulygame‑changing.Squattingbyatermitemound,hepickedabladeofgrassandpokeditintothemound.Whenhepulleditout,itwascoveredwithtermites,whichheslurped down.

Inanotherinstance,GoodallsawDavidGreybeardpickatwigandstrip itofleavesbeforeusingittofishfortermites.DavidGreybeardhadexhibitedtooluseandtoolmaking—twothingsthatpreviouslyonlyhumanswerebelievedcapable of.

WhenGoodalltelegraphedthenewstoLouisLeakey,hesentthis response:

nowwemustredefinetool stop

redefineman stop

oracceptchimpanzeesas human

Leakey’s telegram

FreudcarefullyinspectsGoodall’s hair.

EUROPE

ENGLAND

AFRICA

KENYA

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

TANZANIA