SpreadingtheWord

Goodallbegantopublishherfieldresearch.Yet,shewasmetwithskepticismfromthescientificcommunity.Afterall,shehadnosciencetraining.In1962,GoodallgaveapresentationattheZoologicalSocietyinLondon.Sheimpressedmanypeoplethere.But,otherswerenotimpressed.OnememberoftheZoologicalSocietydescribedherworkas“anecdoteand… speculation”thatmadeno“realcontributionto science.”

Achimpanzeedigsfortermiteswithabladeof grass.

Melissareachesoutherhandto Faben.

ProofPositive

Goodallneededmoreevidenceofherwork.TheNationalGeographicSocietysuggestedshecreateaphotographicrecordofher discoveries.

TheSocietyhiredHugovanLawickforthejob.The25‑year‑oldDutchmanhadsomeexperienceinnaturalhistoryfilmmaking.HereachedGombeinAugust 1962.

AsGoodallandvanLawickdocumentedthechimps’behavior,neitherfocusedontakingpicturesofGoodallwiththechimps.ButNationalGeographicmagazineeditorswantedphotosofheraswell.Theywantedtoshowpeoplehowshestudiedthe animals.

Atfirst,thatmadeGoodalluncomfortable.Shewantedherworktobeaboutthechimpsonly.But,shecametounderstandthatpeoplewereinterestedinher,too.Itwasunusualforawomantobeascientistatthistime.PeoplewereascuriousaboutGoodallastheywereaboutthe chimps!

Lawick’sworkcapturedphotographicproofofthechimpsmakingandusingtools.Healsorecordednestbuildingandhowthechimpsbehavedsocially.AndhetookmanypicturesofGoodalldoingher work.

HisphotographsappearedwithGoodall’swordsinNationalGeographicmagazine’sAugust1963 story,“MyLifeAmongWildChimpanzees:AcourageousyoungBritishscientistlivesamongthesegreatapesinTanganyikaandlearnshithertounknowndetailsoftheir behavior.”

ThecoverofNationalGeographicmagazine,August 1963

ANovelApproach

Theissuewasahugesuccess.In1964,GoodallwassettogiveherfirstmajorpubliclectureintheUnitedStates.Shewasalittlenervousaboutbeingonstageinfrontofthousandsofpeople.ThemembersoftheNationalGeographicSociety’slecturecommitteeseemedevenmorenervous.Astheeventneared,thecommitteeaskedforadraftofherspeech.Shehadn’twritten one!

ButGoodallknewwhatshewantedtosay.Shereportedonherscientificdiscoveries.ShedescribedGombeasbeautifulandpeaceful.Andasshewouldthroughouthercareer,shedescribedchimpsbytheirpersonalitiesandthenamesshe’dgiven them.

ShedescribedFifias“agileandacrobatic”andFifi’solderbrother,Figan,asanadolescentwho“feelshe’salittlebitsuperior.”Goodallnamedonebabychimpwhowas“justbeginningtofindherfeet,”Gilka,afteraNationalGeographiceditor.

achimpnamed Pom

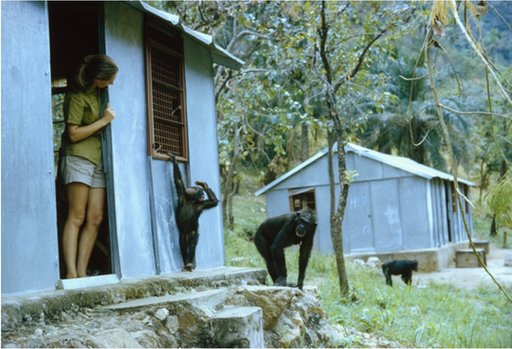

GoodallwatchesFlintfroma doorway.

Indescribingtheneedtoprotectthechimpsandpreventthemfrombeingshotorsoldtocircuses,GoodallreferredtoDavidGreybeard.Hewasthechimpwhohadopenedthedoortosomeofhermostimportant discoveries.

“DavidGreybeard… hasputhiscompletetrustinman,”shetoldtheaudience.“Shallwefailhim?Surelyit’suptoustodosomethingtoensurethatatleastsomeofthesefantastic,almosthumancreaturescontinuetoliveundisturbedintheirnatural habitat.”

Herpresentationwasatriumph.Itwasalsoamilestoneinherbecomingapublicfigure.Thiswasn’tastatusshewaslookingfor.Butshelearnedthatitcouldhelpherdeliverhermessagetomorepeople.Itwasthebeginningofalongandsuccessful career.

JaneGoodall,Continued

JaneGoodallwentontoearnherPh.D.fromCambridgeUniversity.Shehaspublishedmanymagazinearticlesandbooksaboutherresearch.In1991,shefoundedanorganization called

“Roots & Shoots”inTanzania.Itsgoalisto helpyoungpeoplebegincareersinconservationwork.Today,herworkinconservation continues.