Waoranipeopletravelingbycanoeona river.

DrillingDown

In2012,thegovernmentofEcuadorwantedtooffernewdrillingrightstooilcompanies.ThedrillingareaincludedWaoranilands.ThegovernmentwasrequiredbylawtoexplaintheprosandconsofoildrillingtotheWaoraniandothercommunities.So,governmentrepresentativesflewintotherainforestandheldshort,rushedmeetings.ManyWaoranididnothavetimetotravelbyfootorcanoetoattendthesemeetings.TherepresentativesusedtechnicallanguagethatwashardforsomeWaoranitounderstand.Theyspokeonlyabouthowtheoilmoneywouldhelpthecommunity,nothurt it.

Afterward,theWaoranilearnedthatthegovernmenthaddividedupalargesectionoftheAmazon,includingtheirterritory.Thesesectionswouldbeauctionedofftooilcompanies.TheWaoranisectionwasnumber 22.

TheWaoranihaddefendedtheirlandfromSpanishconquistadores,rubbertappers,andloggers.Now,theyneededtodefenditagain.Butfirst,theyneededa leader.

ALeaderforHerPeople

NemonteNenquimoisa35-year-oldmotherwhowasbornandraisedintheWaoraniculture.Earlyinherchildhood,herfathermovedthefamilytoacommunitydeeperintherainforest.Hewantedthemtobeawayfromtheinfluenceofreligiousmissionaries.Nenquimo’schildhoodwasfilledwithswimmingintherainforestrivers,pickingwildfruit,andlisteningtohergrandmother’sandaunt’s

traditional songs.

aWaoranicommunity gathering

ThisWaoranielderusesablowpipeanddartsfor hunting.

Nenquimo’sgrandfather,Piyemo,wasarespectedwarrioranddefenderofWaoraniterritory.Piyemobelievedthattherainforestshouldbeprotectedasaninheritanceforhischildrenandgrandchildren.Fromhim,Nenquimolearnedthatthelandmustbedefendedagainstthosewhodonotmaketheir

homes there.

Nenquimolearnedfromhergrandmother,too.WomenintheWaoraninationhavetraditionallybeenthecaretakersoftheforest.Theywatchovertheplantsandanimalsandtellthemenwheretohuntandforwhichanimals.Nenquimowasalreadyacommunityleader.In2015,shehelpedleadtheWaoraniinaprojecttomaptheirancestral lands.

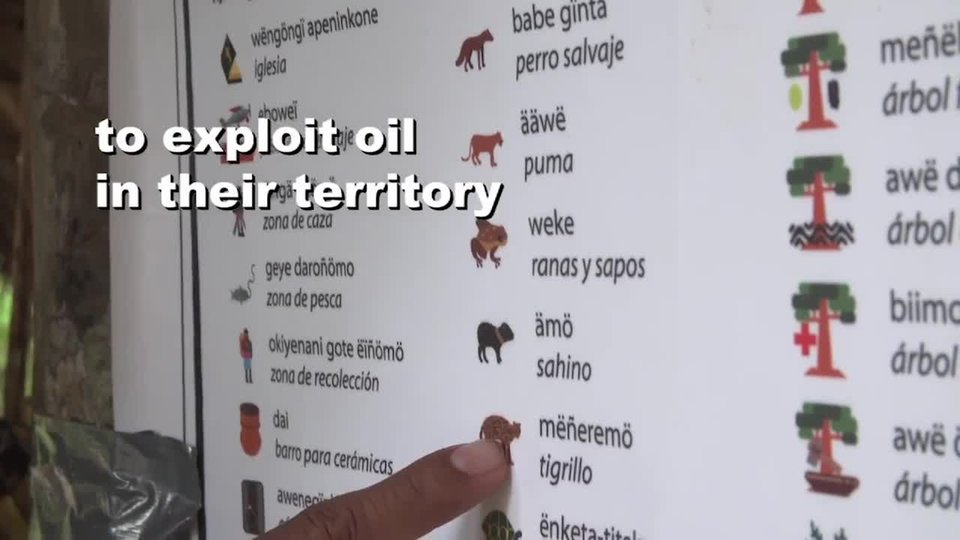

Elders,youngpeople,andchildrenworkedtogethertodrawandmapthesacredwaterways,animalbreedingsites,burialspots,fruittreegroves,andpaintingsontheirlands.Theyusedbothtraditionaldrawingmethods,likepaperandpencils,andmoderndeviceslikeGPSand cameras.

Thesemapswouldprovetobeinvaluableinthelaterfight.TheyshowedthedeeprelationshiptheWaoranihavetotheirlandandhowingraineditisintheir culture.

Surroundedbyherpeople,Nenquimospeakstoreportersaboutthecourt case.

TwelvecommunitieselectedNenquimoandfourotherwomentoleadthelawsuit.ItarguedthatthegovernmenthadnotgottenthefreeagreementoftheWaorani,whichwasrequiredbylaw.Theplannedauctioningofthelandswasillegal.“Thegovernmenttriedtosellourlandstotheoilcompanieswithoutourpermission,”Nenquimosaidlater.“Ourrainforestisourlife.Wedecidewhathappensinourlands.Wewillneversellourrainforesttotheoil companies.”

OnFebruary27,2019,theWaoraniofficiallysuedthegovernmentofEcuador.Theydidnotknowiftheywouldsucceed.But,theyknewtheyhadto try.