FindingSomethingNew

Cabrastakesgreatcarewhenshethinksshe’sfoundsomethingnew.Sheimmediatelysignalstoanyteammatesaroundhertostopmoving.“Igeteverybodytofreeze!”shesays.Shedoesn’twantanysuddenmovementstoscareoffabeetle.Beforemovinganycloser,shetriestotakeaphotographofthescene.“Iusuallytakephotosoftheirfoodplantandhabitat,becauseitgivesnewinformation—notjusttothetaxonomistsbutalsototheecologistsand conservationists.”

Whenthebeetlesfeelvibrationsontreeleaves,theyfalltotheground.Theyareveryhardtofindindead leaves.

teammatesworkingina forest

Manyofthemorethan400speciesofPhilippinejewelweevilshavesmallranges,someastinyasjustonepatchofforest.“Alotofthesespeciesareveryspecifictocertainplants.Theydon’teatavariety,”saysCabras.Thisbecomesimportantifyouhopetoconserve,orprotect,thebeetle.“Youhavetoconservetheirfoodplantifyouwantthebeetlestobe conserved.“

AFullerPicture

There’sanotherreasonwhyCabrastriestorecordthescene:“Forsomeofmycolleagues,thisisthefirsttimethey areseeingthespeciesalive.”Alotofdescriptionsofnewspeciesarebasedonmuseumcollections.So,thetaxonomistscategorizingandnamingspecies haveneverseenthosespeciesaliveorinthewild.Theyhaveneverseentheirhabitatsorhost plants.

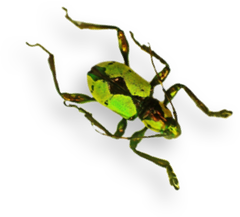

Thisbeetle,Pachyrhynchusreicherti,wouldbecomeimportanttoCabras’research.Shesoondiscoveredanewspeciesthatlooked similar.

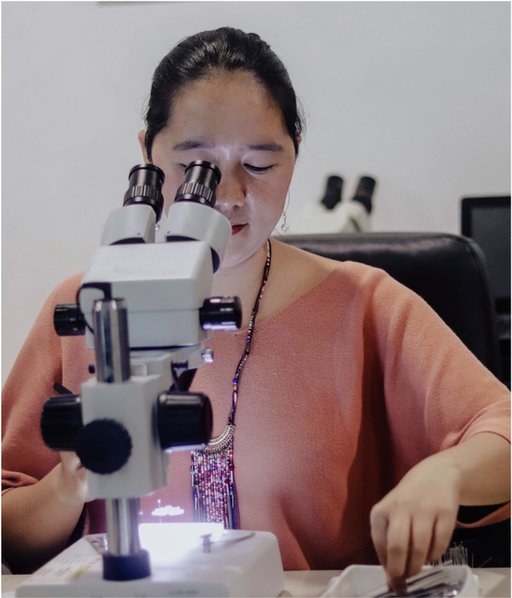

Cabrasusesapowerfulmicroscopetocloselyexaminebeetle specimens.

Ifpossible,Cabrasthencollectsabeetleasasamplesothatitcanbelookedatmorecloselyinthelab.“Whenyouareinthelaboratory,it’sthesamething—youhavetophotographthem.Youexamine[their anatomy.],”shesays.Thelabworkrequirestremendouspatiencebecausethebeetlesareso small.

That’snotall.“Italsorequiresspecialskillsandyearsoftrainingtodothelabwork.Youhavetotrainyoureyestolookintothemicroscope,butyoualsohavetotrainyourhands.”Beetlesmustbedissected,orcutapart,soscientistscanseetheirinternalstructures.Thatrequiresgoodeyesandsteady,steady hands.

Yet,evenwithhergoodeyesandsteadyhands,Cabrascan’talwaystrustwhatshesees.Sometimesevenshecanbe fooled.

WeevilWonders

Jewelweevilsaresonamedbecausetheysparklelikegems.Theirelytra,orwingcovers,shimmerwithanarrayofcolors—frombrilliantturquoiseandshinygoldtopaleorangeandpink.Withsuchnoticeablecolors,you’dthinkthey’dbeeasytargetsforpredatorslikefrogs,lizards,andbirds.Butweevilswanttobeseen.Theircolorsactasawarning:Don’teatme.Itaste bad.

There’sawordforthisinscience.It’scalledaposematism.Itistheadvertisingbyananimaltopotentialpredatorsthatitisnotworthattackingoreating.Aposematismcantaketheformofbrightcolors,sounds,odors,orothercharacteristics.Thesesignalsarehelpfultobothpredatorandprey,sincebothavoidpotential harm.

Cabrasknewallaboutaposematism,butshedidn’trealizehowmuchitwasgoingtoaffectherweevil research.

Chrysopidasp.isaleafbeetlethatlookslikesomejewel weevils.