ChallengingLandscape

Birdsaren’tfurryandcuddly,butinmanyrespects,they’remoresimilartousthanothermammalsare.Theybuildintricatehomesandraisefamiliesinthem.Sometakelongwintervacationsinwarmplaces.Manyhaveacomplexlanguagefor communicating.

Thereis,however,oneabilitythathumans havethatbirdsdonot.Birdscannotcontroltheirenvironment.Theycan’tprotectwetlands.Theycan’tmanageafishery.Theycan’tair-conditiontheirnests.Theyhaveonlyinstinctstohelpthemsolveanyproblemstheyencounter.

Insoaringflight,theMalayancrestedserpenteagleholdsitsbroadwingsinashallow“V”togiveitspeed.

Theseinstinctshaveservedbirdswellforalongtime—150millionyearslongerthanhumanshavebeenaround.Butnowhumansarechangingtheplanet—itssurface,itsclimate,itsoceans.Thesechangesarecomingtooquicklyformanybirdstoadapt.Thefutureofmostbirdspeciesdependsonourcommitmenttopreservingthem.Aretheyvaluableenoughforustomaketheeffort?

Mostbirdswitheyesonthesidesoftheirheads,liketheMalayancrestedserpenteagle,haveawidevisualfield.That’susefulindetectingpreyandkeepingawatchfor predators.

Thebare-facedgo-away-birdwasgivenitsfunnynameforitsfeatherlessface.Butit’sthetall,featheredplumeonthetopofitsheadthatattractsthemostattention.

TheValueofBirds

Abird’svaluemightdependonhowwemeasurevalue.Sometimeswevaluesomethingbecauseitisuseful.Certainly,manytypesofbirdsarevaluabletousbecauseweeatthem.Somebirdsarevaluablebecausetheyeatinsectsandrodents.Manybirdsperformvitalroles—pollinatingplants,spreadingseeds,orservingasfoodforpredators.

Butonereasonthatwildbirdsmatter—oughttomatter—isthattheyareourlast,bestconnectiontothenaturalworld.

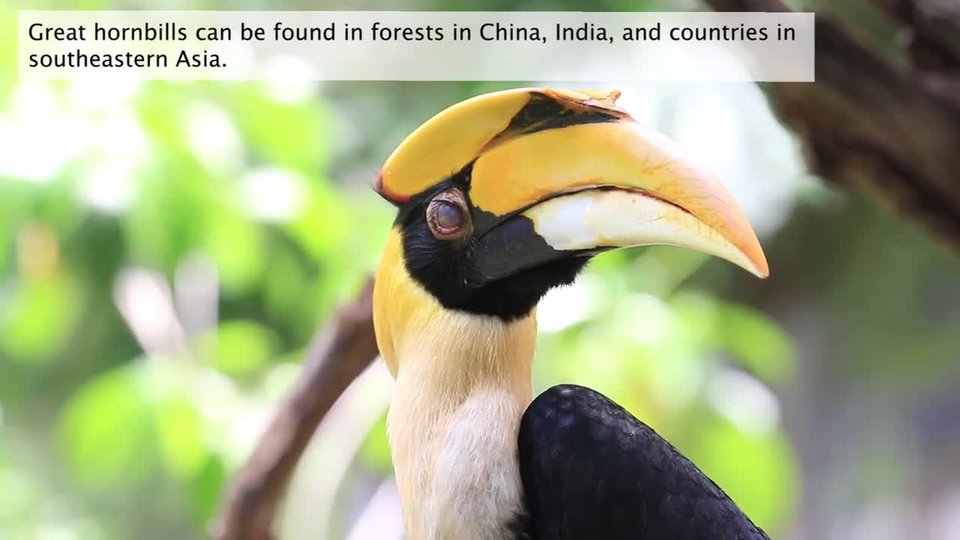

Afewyearsago,IwasinaforestinnortheastIndia.Suddenly,Iheardandthenbegantofeelinmychest,adeeprhythmicwhooshing. Itwasthewingbeatsofapairofgreathornbills.

Therainbowbunting’sbrightcolorsimpresspotentialmates.

Thehornbillswereflyingtoatreewithfruit.Theyhadmassive,yellowbillsandhefty,whitelegs.Theylookedlikeacrossbetweenatoucanandagiantpanda.Astheyclimbedaroundinthetree,Icriedoutwithjoy.MyjoyhadnothingtodowithwhatIwantedorwhatIpossessed.Itwasthesheerpresenceofthegreathornbill,whichcouldn’thavecaredlessaboutme.

Birdsarealwaysamongus.Yet,theirindifferencetousoughttoserveasareminderthatwe’renotthemeasureofallthings.Birdslivesquarelyinthepresent.Andatpresent,theirworldisstillverymuchalive.Ineverycorneroftheglobe,innestsassmallaswalnutsoraslargeashaystacks,chicksarepeckingthroughtheirshellsandintothelight.