SoleBrothers

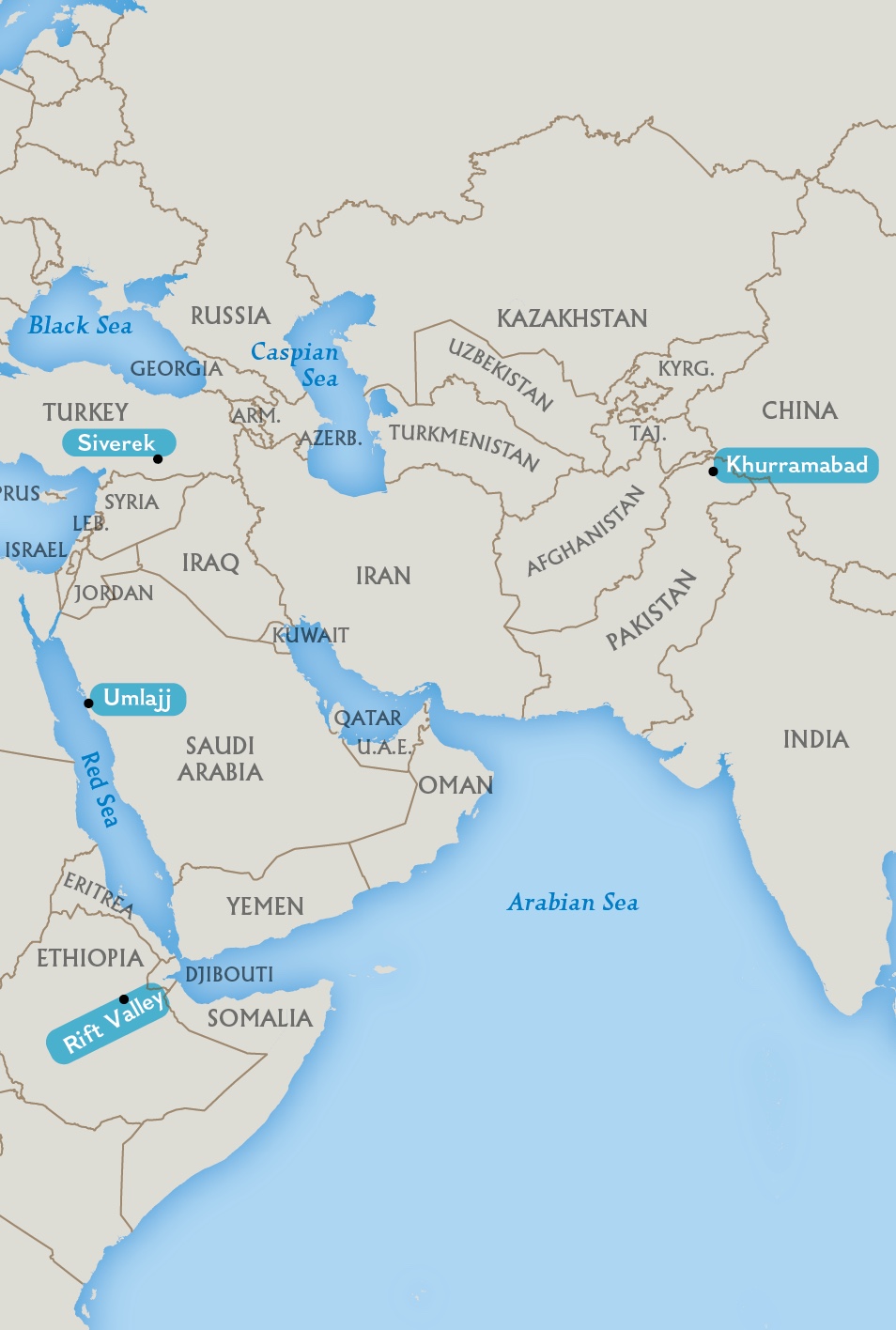

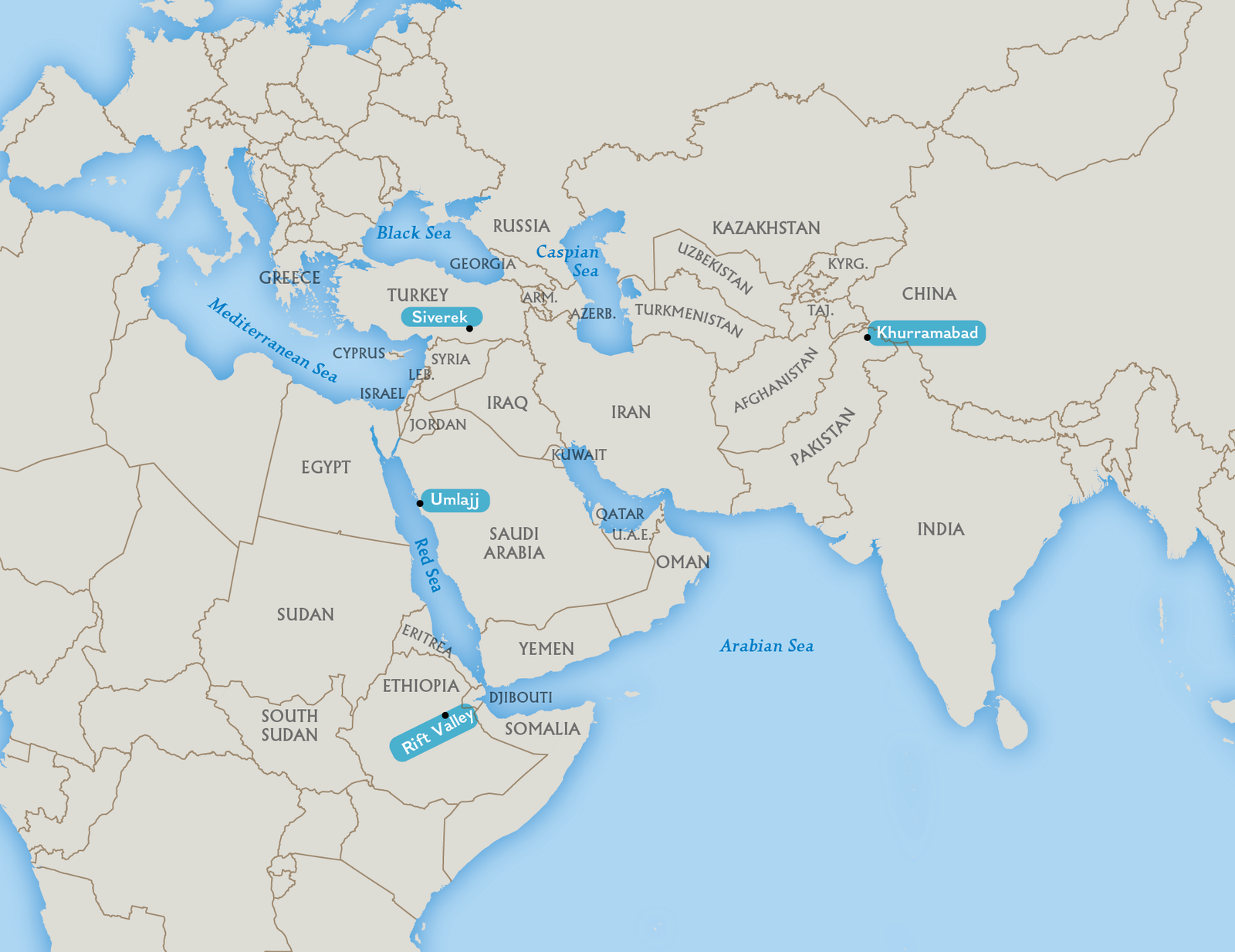

RiftValley,Ethiopia

January31,2013

Salopek’stripwillrequiremillionsofsteps,sohisfootwearisprettyimportant.InEthiopia,therearefew options.

Howdoyoumeasureaman?Lookathisshoes.Shoesannouncetheirwearer’sclass,style,evenjob.Itisdisorienting,then,tobewalkingthroughaplacewherehumanbeings—millionsuponmillionsofwomen,men,andchildren—sliponidentical-stylefootweareverymorning.Theyarethecheap,versatile,plasticsandalofEthiopia.Manypeoplearepoor,sotheybuyandwearwhattheycanafford.Povertydrivesdemand.Theonlybrandis necessity.

Acoupleofmycamelhandlersforthisportionofmyjourneyeachworematchinglime-greenplasticsandals.ThesurfaceoftheRiftValleyiscoveredinfootprintsstampedinthedustbymillionsoftheseplasticshoes.YetifEthiopia’spopularsandalsaremass-produced,theirwearersare not.Theydragtheirleftheel.Theyruintherightshoe’smoldingbysteppingonan ember.

Ourguidekneltdowntheotherdayonthetrail,examiningtheshoes’endlessimpressions.Hepointedtoasinglesandaltrackandsaid,“La’adHoweniwillbewaitingforusinDalifagi.”Andsohe was.

MillionsofEthiopianswearthesamestyleofshoe,madefrommoldedplastic.

Awad’sRefrigerator

Umlajj,SaudiArabia

October30,2013

Salopekandhisguidesmustcarryeverythingtheyneedastheytrekfordaysandweeksatatime.Carryingwateracrossthedesertisessential.Butwhosaidanythingaboutitbeing cold?

Whenthefirst modern Homosapiens, ormodernpeople,walkedoutofAfricaandintotheArabianPeninsula,theregion’sseaswereloweranditshillsgreener.Thedetailsofwhatthesewanderersexperienced,wedonotknow.Whatisundeniablewastheirneedtocarry water.

Theweightofwaterisasensoryexperience.Waterisheavy.Itweighsfourkilograms(ninepounds)per3.8 liters(onegallon).Tocarryenoughofthisvitalsubstanceforgreatdistancesrequiresstrengthandingenuity.Whatdidthefirsthumanramblersuseascontainers?Nobodyknows.Canteensorbucketsmadeofnaturalmaterials?Perhapstheycarriedwaterinagurba—agoatskinwaterbladder.AwadOmran,mySudanesecamelhandler,hasasolutiontoconqueringtoday’sthirst.

Awad’scold-watercanteen:burlapricesack,cardboard,plastictwine,knife,needle,plasticwater bottle.

Omranspends20minutesbuildingawater-coolingthermos.It’smadeentirelyfromfoundmaterials—pilesofjunkdiscardedaroundafarm.Hewrapsalargewaterbottlewithcardboard.Hewrapsthecardboardbundleinpieceofburlapthatonceheldrice.Hemakesalonghandlefrom twine.

Awad’swaterrefrigeratoroperatesonthesimpleprincipleofevaporation.Wettedandhungonacamelsaddle,itsdampenedcardboardinsulationcoolsourdrinkingwaterbyseveraldegrees.Werefillit constantly.

Mule-ology

NearSiverek,Turkey

December11,2014

Salopekrarelytravelsalone.He’susuallyjoinedbyalocalguideandapackanimalortwotohelpcarrysupplies.Here,hewritesabouthismulewhiletravelingthroughTurkey.

Firstthingsfirst:Amuleisnotadonkey.Inmyopinion,adonkeyisamemberofthehorsefamilyburdenedbylowself-esteem.It’sasmall,modest,long-earedcreaturefromwhichmulesarebredwhenmatedwithahorse.Amuleissomethingelseentirely.Tocallamuleadonkeyisfighting words.

Therearejack mules(male)andjennyormollymules(female).Therearebluemules,cottonmules,sugarmules,andmining mules.

ButtheonethingI’velearnedisthatitdoesn’tmatterwhatyoucalla mule.Mulesdonottolerate names.

Ourwhitejenny,forexample,hasbeenbaptizeddifferentlybyeachofmywalkingpartnersacrossTurkey.OneguidecalledherBarbara,forreasonsonlyhecanexplain.AnotherdubbedherSunshine.StillanothercalledherSweetie.JohnStanmeyer,myphotographer,referstoheras Snowflake.

MypreferenceisKirkatir,aTurkishnamemeaning“greymule.”Thetruthisthat,likeallmules,sheanswerstonolabelhandedoutbyhumans.Kirkatirdoesnotcomewhencalledorwhenwhistledto.Shecomeswhenshefeelslikeit.Thisisnotveryoften.

Kirkatirdoeswhatshepleasesandwhenshepleases.Sheplodsalongatherownpace,shoulderingtheburdenofoursupplies.Andforthat,weare grateful.

PaulSalopek’smuleinTurkeymaynotcomewhencalled,butsheshouldersmuchoftheburdenonthewalk.

WalkingGrass

NearKhurramabad, Pakistan

January02,2018

Alonghistravels,Salopekencountersmanypeoplegoingabouttheirdailylives.Here,inPakistan,hecomesacrosssomefarmersharvestingandcarrying hay.

ThemountainrangethatcutsnorthernAfghanistanfromPakistanisacolddesert.Thereislittleprecipitation.

Foralltheirthickglaciersandsnowpack,thetoweringmountainsareparched.Inthelatesummers,glacialmeltstreamsdown,washingawayvillages,roads,and topsoil.

Thepeoplewhocallthisstarklandscapehome—manyofthemfarmers—readythemselvesforfall.Everyautumn,astheirpasturesdrytothecolorofgoldandcopper,villagersharvestwild hay.

Youcanseethemwalkingfasttoshortentheagonyundertheirheavyloads.Theylooklikehumanantstotinghuge bundles.

RehmanAliandBibiPariareoldernow.Theirsonshavegrownandmovedtolargercities.Buttheyremainandharvesttheirslopedandrockyfieldsbythemselves.Pari,thewife,standsnohigherthanmybicep.Hernamemeansfairy.” I canhardlybudgehercargo,butsherocksitswiftlytohershoulders.“Thankyou,brothers,”shesaystous,fortheridiculousactofwatchingher work.

Afarmercarriesnearly45kilograms(one hundredpounds)ofhaytohishouseabout

3.2kilometers(two miles)away.