Thesceneisoftendescribed:

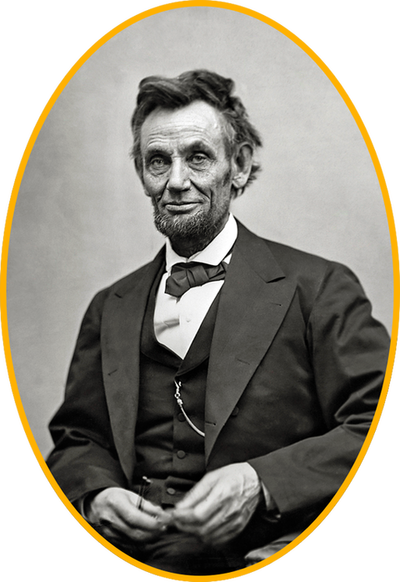

OnthenightofApril14,1865,PresidentAbrahamLincolnwenttoFord’sTheatre.HeandMrs. Lincolnsatinaspecialboxabovethe stage.

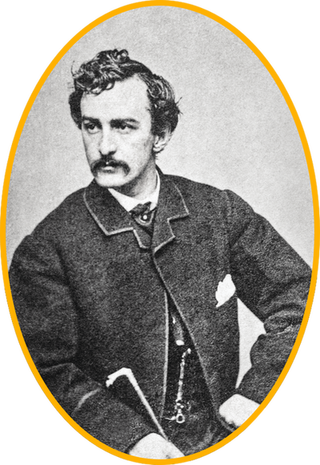

Duringtheplay,amanenteredthebox.HewasafamousactornamedJohnWilkesBooth.BoothwasupsetoverhowtheCivilWarhadended.HeblamedLincoln.HeaimedagunatLincolnandfired.Whatfollowedwas chaos.

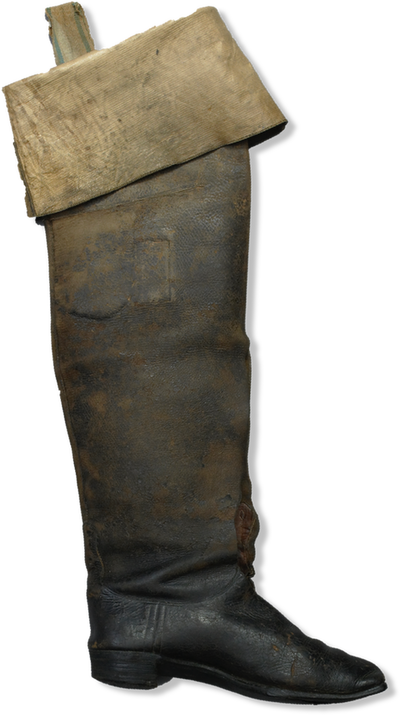

Tomakehisescape,Boothleapedfromthepresident’sboxontothestage.Onthewaydown,Booth’sbootcaughttheedgeofadecorativeflag.Hestumbledashelanded,breakinghis leg.

“Sic semper tyrannis! ” heshoutedtothepanickedaudience—Latinfor“Thusalwaystotyrants.”Hefledthestageandjumpedonhiswaitinghorse outside.

Morethan150yearshavepassed,buttheeventsofthatnightremainfresh—especiallyforthosewhovisitFord’sTheatretoday,inpersonoronline.Manyoftheartifacts,orobjects,fromthatnighthavebeencarefullypreserved.Theseitemsareapowerfullinktoourpast.Theyhelpuslearn,andtheyhelpus remember.

oneofthebootsJohn Wilkes Booth wore

PreparingforImportantGuests

TheflagthatBoothcaughthisfootonisonesuchitem.Thatmorning,amessengerfromtheWhiteHousehadcometothetheatertorequestticketsfortheevening’sperformance.Thepresidentandfirstladywouldmakeimportant guests.

JamesR.Ford,brotheroftheaterownerJohnT.Ford,quicklyvisitedtheTreasuryDepartmenttoborrowfiveflagstodecoratethepresidentialbox.Fouroftheflagsweretheregular,36‑starAmericanflagsoftheday.Thefifthflagsportedahand‑paintedeagleemblemondarkbluesilk.Thisflagwasanchoredtothemiddleoftheboxbya flag pole.AsBoothfell,hisspurtoretheedgeoftheflag—atearthatremains today.

NowkeptunderglassattheNationalParkService’sMuseumResourcesCenterinMaryland,theflagisoneofmorethansixmillionartifactstobecaredfor.TheyareallobjectsofhistoricsignificancefrominandaroundWashington,D.C.TheycomefromsuchplacesasFord’sTheatreorfrom thehomeofabolitionistFrederick Douglass.

Onlyasmallnumberofitemscanbeshowninmuseumsandothersites.Somearetoofragile.Others,toolarge.Mostly,therearejusttoomanytodisplay.Whatcannotbedisplayedmustbecarefullystoredinasafe,secure,andenvironmentallystable way.

Boothcarriedthiscompass duringhis escape.

Ford'sTheatre

Ford’sTheatreopenedinAugust1863.Aftertheassassination,thetheaterwasclosed.Thenthebuildingwasusedasawarehouseandofficebuilding.In1893,partofit collapsed.

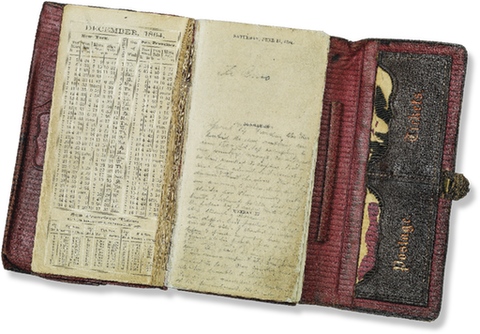

Itwasrenovatedandreopenedasatheaterin1968.However,thepresidentialboxisneveroccupied.TheFord’sTheatreMuseumbeneaththetheaterhasmanyitemsthatarerelatedtotheassassination,includingthepistolBoothusedandBooth’s diary.

Booth'sdiaryistheonlyrecordofhispersonalthoughtsafterthe assassination.

Powellhadhistoothbrushwithhimwhenhewas arrested.

ThecollectionalsoincludesThomasPowell’stoothbrush.Whowasheandwhydoesthemuseumdisplayhis toothbrush?

PowellwasaConfederatesoldier.HeconspiredwithJohnWilkesBoothtoharmthepresidentandothermembersofLincoln’s cabinet.

Atoothbrushmightseemlikeastrangeartifactforamuseum,butsometimesordinaryobjectstakeongreatermeaningwhentheyareconnectedtoaninfamouspersonor event.

Inthiscase,thetoothbrushwasusedasevidenceagainstPowellduringhistrial.Anotherco‑conspiratortestifiedthatPowellalwayscarriedhistoothbrushwith him.

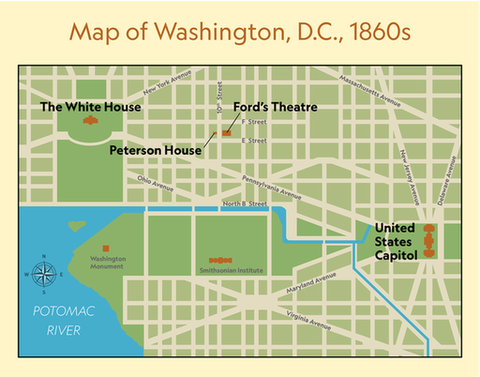

MapofWashington,D.C.,1860s

TheWhite House

Peterson House

Ford's Theatre

UnitedStates

Capitol

Smithsonian Institute

Washington

Monument

POTOMAC RIVER