Searchingfor Solutions

So,whatdowedotostopthislionfishinvasion?Peopleareworkingonwaystoaddressthecrisis—scientists,divers,evenchefs.Yes,chefs.Butwe’llgettothatina minute.

Let'sstartwiththescientists.Lionfishdon’thaveanynaturalpredatorsintheAtlanticOcean.So,somescientiststriedtosolvetheproblembyteachinglocalpredatorstolookatlionfishas lunch.

Adiverwouldspearalionfishandthenofferupthemealtoanearbybarracuda,eel,orshark.Itseemedlikeagoodidea,butithadafewdrawbacks.Whilethepredatorswouldgladlyeatthelionfishtheywereoffered,mostofthemdidn’tstarthuntinglionfishontheirown.Theyexpectedhandouts.Andsomespecies—especiallysharks—begantogetaggressivewith divers.

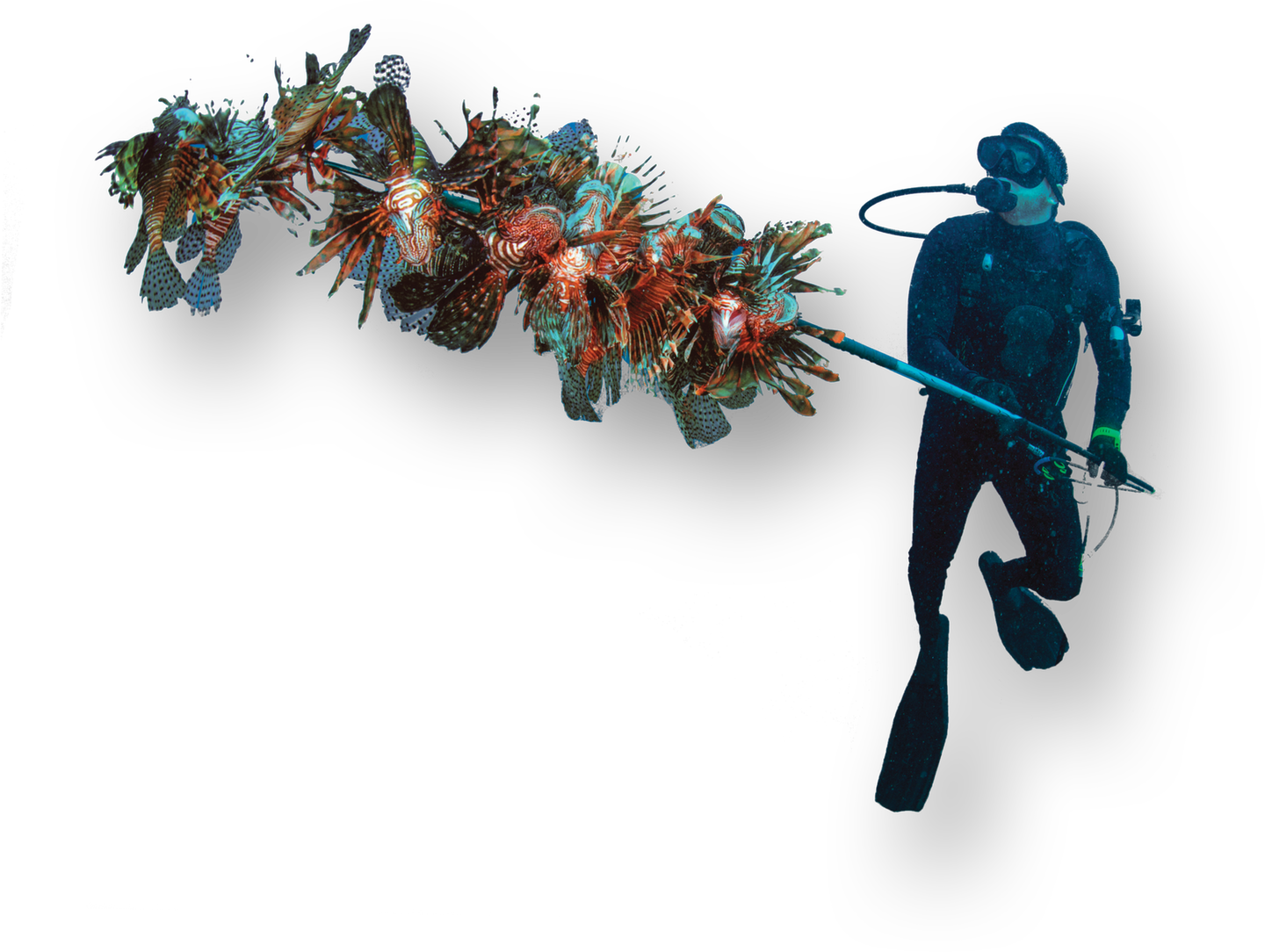

A diverspearsmanylionfishduringalionfish "derby."

FishingTournaments

Divershavehadabitmoreluckmanagingtheproblem,downtocertaindepths,throughlionfish “derbies.”

Alionfishderbyisacompetitiontocollectandremoveasmanylionfishatagivenplaceaspossible.TeamsofdiversSCUBAdive,freedive,orsnorkel.Theynetlionfishorspear them.

Eachlionfishismeasured,andprizesaregivenoutforteamsthatcatchthemost,thebiggest,andthesmallestlionfish.Thepublicisinvitedtoattendthecompetition.Theycantastefreelionfishsamplesandlearnmoreabout lionfish.

From2009to2018,theReefEnvironmentEducationFoundation(REEF)hostedderbiesthatremovedmorethan23,000 lionfishfromspecific sites.

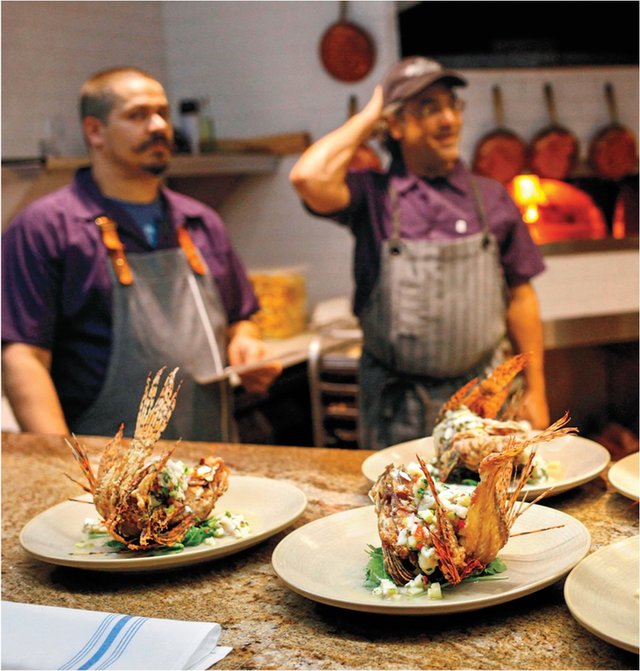

Chefspreparenewlionfish recipes.

AFishyFare

Despitetheirtroublesomespines,lionfisharenotpoisonous.Theyarevenomous.Thedifferencebetweenpoisonandvenomisthemethodofdelivery.Poisonhastobeeatenorabsorbedtobeharmful.Venommustbeinjectedintothebloodstreamtocauseinjury,suchasthroughasharpspineorfang.Yet,itisharmlessif consumed.

Giventhat,somechefshaveadoptedastrategyof“ifwecan’tbeatthem,eatthem.”In2010,REEFreleasedacookbooktogetcommercialdiversandchefsinterestedinlionfish.Chefsatmanytoprestaurantshavetriedtofindcreativewaystoofferthisnewcuisinetotheircustomers.However,buildinganindustryaroundthesefishishard.Theydon’tbiteonhooks.Andtheycan’tbecaughtusinglarge nets.

SettingaTrap

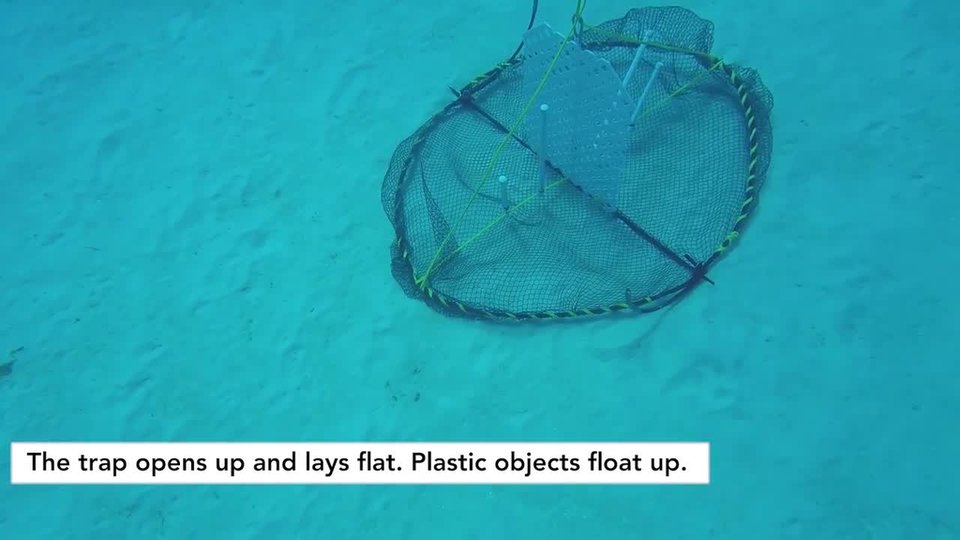

SteveGittings,achiefscientistattheNationalOceanicandAtmosphericAdministration'sNationalMarineSanctuarySystem,mayhaveyetanotherstrategytodealwithlionfish.Heisfocusedontrappingthembyusingtheirnaturaltendenciesagainst them.

Lionfishliketogatheringroupsaroundunderwaterstructures.So,Gittingsdevelopedatrapthatworkslikeachangepurse.Nettingisattachedtotworoundedsidesofthe“purse.”Whenthetraphitsanoceansurface,itspringsopenandlays flat.

Insidethetrap,afewplasticobjectsfloatup.Theseobjectsattractlionfish.Thetrapstaysopenforawhile.Otherfishcomeandgo.Butlionfishtendtohangoutatthetrap.Finally,afishermantugsonthetrap.Thepursequicklycloses,shuttinganylionfish inside.