ToProtectandPreserve

Toprotectandpreservesuchvaluableitemsisabigresponsibility.Curatorsaretrainedtodealwiththedangers.Lightdamageisoneofthemostseriousthreats.Bothvisibleandultraviolentlightrayscanbeharmfulbyfadingobjectsandbreakingdownfibers.Theflagfromthepresidentialboxisatrisk.Itismadeofsilkthathasbeendyeddark blue.

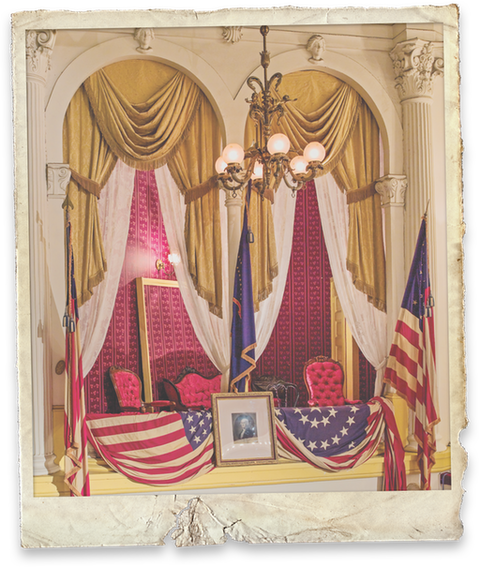

flag

Darkfabricdyescanbeacidic.Whenexposedtolight,theacidscanfadethefabricquickly.Thefibersofthefabricalsobegintobreakdown.That’swhycuratorsputtheflagunderspecialglassthatblocksultravioletlight.Framingtheflagalsoensuresthatitwillbekeptflat.Foldingtheflagcouldcreatelastingcreases.Historicfabricsareoftenrolleduptopreventsuch damage.

Otherdangerscomefromtheenvironment.Dirt,dust,bodyoils,andotherpollutantscandestroyobjects.That’swhycuratorsusewhitecottonglovestohandleanyartifact.Curatorsalsohavetoworryaboutpests.Rodentsorbugsmighttrynibblingonartifactsorevenusingthemtobuild nests.

Changesintemperatureandhumiditycancausedamage,too.Curatorsmustlookforsignsofwarping,shrinkage,mold,mildew,orrust.Allartifactsarekeptinaclimate‑controlledenvironmenttopreventthosetypesofdamage.Thecenterisalsoequippedwithanadvancedfireprotection system.

NationalParkServicemuseumcuratorKamalA. McClarinwearscottongloveswhenhehandlesartifactsliketheflagfromthepresident'sboxatFord's Theatre.

tear

ThePathtoPreservation

Insomecases,artifactscomeintoamuseum’scollectionquickly—soonaftertheeventthatmadethemspecialoccurs.Inothercases,manyyearscan pass.

AfterPresidentLincolnhadbeenshot,hewascarriedacrossthestreettothehomeofWilliamandAnnaPetersen.BecauseLincolnwassotall,hehadtobelaiddiagonallyacrossabedinoneofthebackbedrooms.ItwastheroomofayoungarmyclerknamedWillieClark.Clarkwasnothomeatthe time.

Soldierswerepostedatthedoorsofthehouseandontheroofwhiledoctorsfranticallyattendedtothewounded president.

Thepresidentwouldnotrecover.At7:22 a.m.onApril 15,AbrahamLincolndiedfromhis wound.

WhenClarkreturnedthenextmorning,hisroomwasinshambles,andthepresidentwasgone.Thatnight,Clarkclimbedintobedtosleep—thesamebedthathadhoursbeforeheldthe president.

bedroomatPetersonHouse,

locatedacrossthestreetfromFord’s Theatre

WillieClark'slettertohissisterhasbeencarefully preserved.

Fourdayslater,Clarkwrotealettertohissister,Ida.Init,hedescribedwhatwashappeningatPetersen House.

Hewrote:“Sincethedeathofourpresidenthundredsdailycallatthehousetogainadmissionintomyroom....Everybodyhasagreatdesiretoobtainsomemementofrommyroomsothatwhoevercomesinhastobecloselywatchedforfearthattheywillsteal something.”

Clarkhimselfmanagedtotakeafewitemsasremembrancesbeforehemovedoutafewdayslater.Hesenthissistersomethingofgreatvalue.He wrote:

“EnclosedyouwillfindapieceoflacethatMrs.Lincolnworeonherheadduringtheeveningandwasdroppedbyherwhileenteringmyroomtoseeherdyinghusband(.) Itisworthkeepingforitshistorical value.”

Thepieceoflacedisappearedordisintegratedlongago.Buttheletterremained.ItstayedintheClarkfamilyuntilitwasdonatedtoFord’sTheatre,morethan100years later.

AbrahamLincolnworethiscoat,vest,andtrousersashisofficesuitwhilehewas president.

ThisexhibitshowsthecoatAbrahamLincolnworethenighthewas shot.

HistoriansconsiderClark’slettertobeofgreatvaluebecauseitisafirst‑handaccountoftheaftermathoftheassassination.Itiswhatisknownasaprimary source.Aprimarysourceisanartifact,document,diary,manuscript,autobiography,recording,oranyothersourceofinformationthatwascreatedatthetimeunder study.JohnWilkesBooth’sdiaryisalsoaprimarysource.Itis,infact,theonlysourcethatrecordedBooth’sthoughtsatthe time.

TheFord’sTheatrecollectionisfullofinterestingartifacts.YoucanseetheclothesLincolnworetothetheaterthatnight;aplastercastofLincoln’sfacemadeafewmonthsbeforehewaskilled;piecesofevidenceusedagainsttheconspiratorsduringtheirtrial;andmanyother objects.

Thesepiecesofourpastareanimportantpartofourhistory.Eachobjecthasitsownstory.Butalloftheseitemshavebeencarefullypreservedandprotectedsothatpeoplecanstillseeandconnectwiththem today.

TofindoutmoreabouttheartifactsatFord’sTheatre,goto www.fords.org

TolearnmoreabouttheNationalParkService’sMuseumResourcesCenter,goto www.nps.gov/orgs/1802/

MyCareer

WhennothandlingartifactswithhiswhiteglovesattheMuseumResourcesCenter,KamalMcClarincanbefoundatdifferenthistoricsitesintheWashington,D.C.,area.McClarinservesasan interpretiverangerwiththeNationalPark Service.

It'shisjobtohelpvisitorsmakeapersonalconnectionwithhistoricplacesandpeople.He'softenworkingatthehomeofFrederickDouglass.Douglasswasaformerslavewhobecameanabolitionist.HepressedPresidentLincolnforequalityforallpeople.McClaringivesvisitorsasenseofhowDouglasslivedand worked.