flowersinGeorgeWashington's garden

It’ssummer.I’mstandinginGeorgeWashington’sgarden.Idon’tthinkhe’dmind.He’sbeendeadformorethan220years!Butthegardenisstillhere.It’sonhisestate,MountVernon,inVirginia.Thegardentodayisalotliketheoneourfirstpresidentenjoyed.Howdidresearchersfindoutwhatto plant?

Theylearnedaboutthepastbystudyingprimarysources. That’ssomethingthatwascreatedatthetimetheyarestudying.Theyalsoturnedto artifacts likejournalsorfarmingtools.Naturecanalsobeusedasaprimary source.

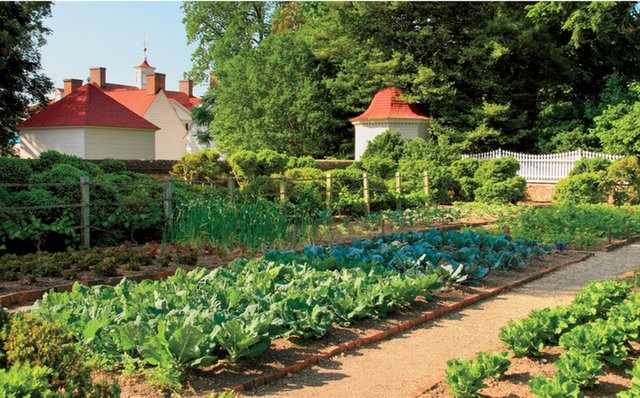

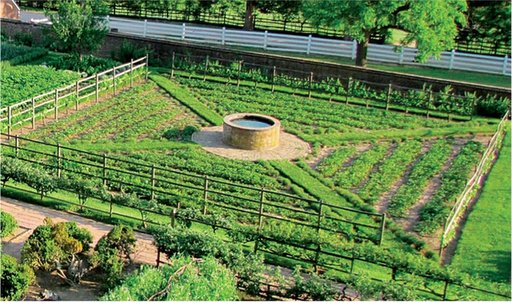

TheGeneral’sGarden

Writingcantellusalotaboutthepast,butnoteverything.InthecaseofMountVernon,therearefewwrittenrecords.Washingtonkeptsomenotes.Weknowthattherewerefourmaingardensonthe grounds.

Washingtonaddedrowsofvegetablestoeachplanting bed.

Boxwoodswerecutintofancy shapes.

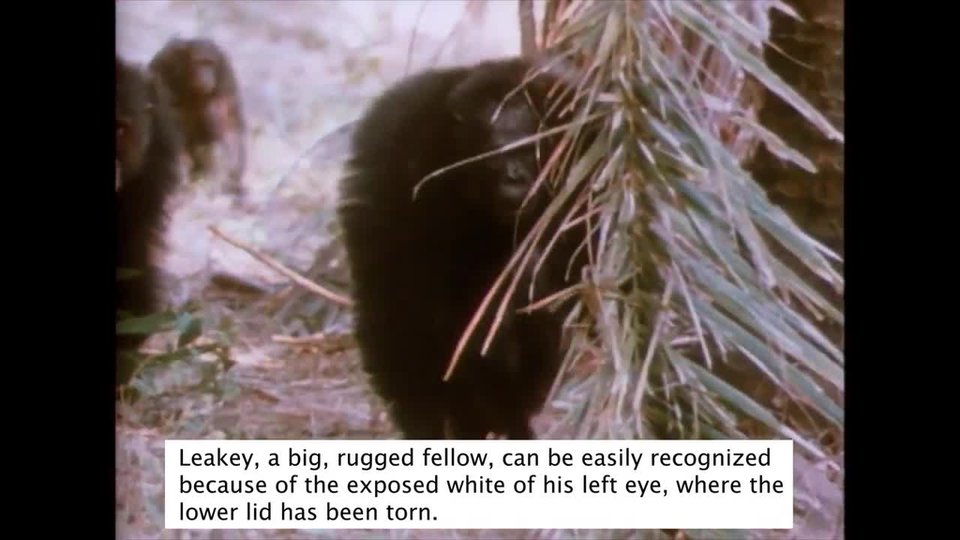

Theuppergardenwasfilledwithflowers,bushes,andexotictrees.ThisformalgardenprovidedaspaceforWashingtontoentertain guests.

Fruitsandvegetablesgrewinthelowergarden.Thisgardenwasjustfor food.

Washingtonusedanothersmallgardenasalaboratory.HetesteddifferentplantstoseeiftheycouldgrowwellinVirginia’s soil.

Lastly,Washingtonhadafruitgardenandnursery.Hewantedtohaveavineyard.Butgrapesdidnotgrowwellonhis land.

ThelowergardenwasusedtogrowfoodforMount Vernon.

UPPER

GARDEN

LABORATORY

GARDEN

LOWER

GARDEN

FRUITGARDENAND NURSERY

mapofMount Vernon

TendingtheGarden

Washingtondidnottendtothesegardensalone.Enslavedpeopleworkedthelandforhim.Theywereabletoreadandwrite.Sotheyalsokeptlistsandmadedrawingsofwhatwas planted.

Researcherstodaycheckedthewrittensources.Theycheckedothersources,too.Theylookedatthe soil.

AtMountVernon,scientistscananalyzesoiltolearnaboutitsfertility.ThiscantellwhycertainkindsofcropsgrewatMountVernon.ItcanalsogivecluesaboutWashington’sfarmingpractices.Researcherswantedtoknow more!

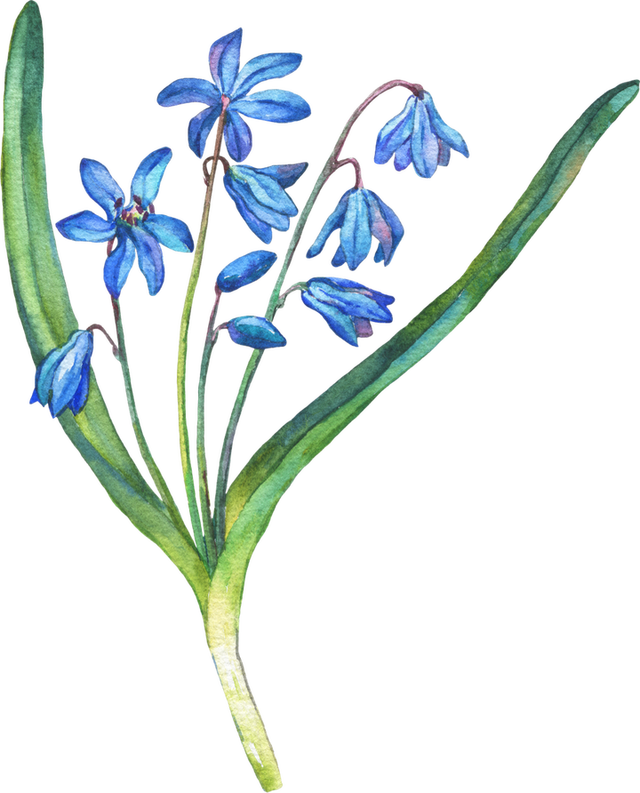

adrawingofalpinesquill wildflowers

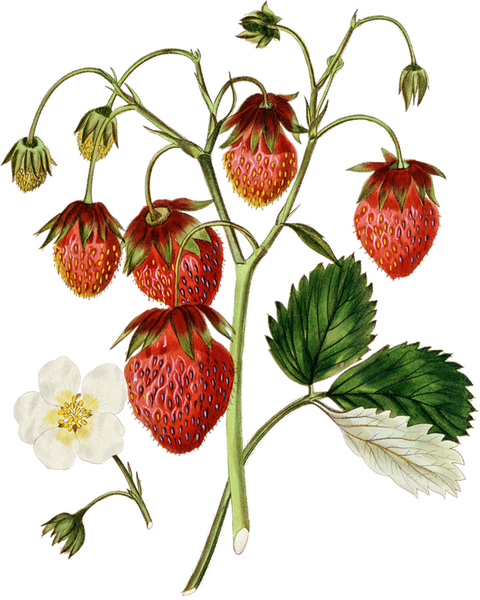

Inaletterfrom1798,afriendsentWashingtonafewscarletalpinestrawberry seeds.

Thegardenwasregrownin1985,butitwasnotlikeWashington’sgarden.Theteamwantedtomakethegardenlookliketheoriginal.TheylookedataseriesofplansdrawnbyaplanternamedSamuelVaughan.HevisitedMountVernonin 1787.