So,thereIwasinaremotepartofGreenland,holdingatinybirdcalledalittleaukinmyhand,waitingforittopoop.Nowbeforeyouask,theanswerisno.No,thisisnotwhatIexpectedtobedoingonmyfirstmajorresearch expedition.

a little auk

Ihaditallplannedout.Asamarinebiologist,Iwasgoingtostudywheretheselittleseabirdsweregettingtheirfoodfromtheocean.Ihadputtrackingdevicesonthebirds.Theylooked likeelectronicbackpacks.Theidea wastoretrievethebackpackswhen thebirdscamebackfromtheirfood runs.ThenIcouldalsoretrievethe data,showingmewheretheyhad

flowntowhileoutto sea.

Ihadn’tcountedonthetrackersfallingoffofthebirdsandgettinglost intheocean.But,that’sexactlywhathappened.Ipanicked.Myentireresearchprojectwas ruined!

Or,wasit?Ihadtothinkfast.HowcouldIsalvagethisexpedition?Andthenitcametome:Imaynotbeabletotrackwheretheygottheirfood,butIcouldcertainlyanalyzewhatthebirdshad eaten.

So,asthebirdscamebacktoland,Igentlyheldthemovermynotebookandwaited.Whenabirdpooped,Ihadmysample.Ididthis110timesfor110samples.Who saidscienceisn’t glamorous?

Itookallmygloriouspoopsamplesbacktothelabtoseewhatthebirdshadeaten.Whilewaitingformorefundingtohavemysamplesanalyzed,Icameacrosssometroublingnews.Anotherresearcherhaddiscoveredthatlittleaukparentswerebringingback plastic fortheirchickstoeat.Todiscoverthatplasticpollutionwaspresentinsuchremotewaterswasashock.Itwasaturningpointfor me.

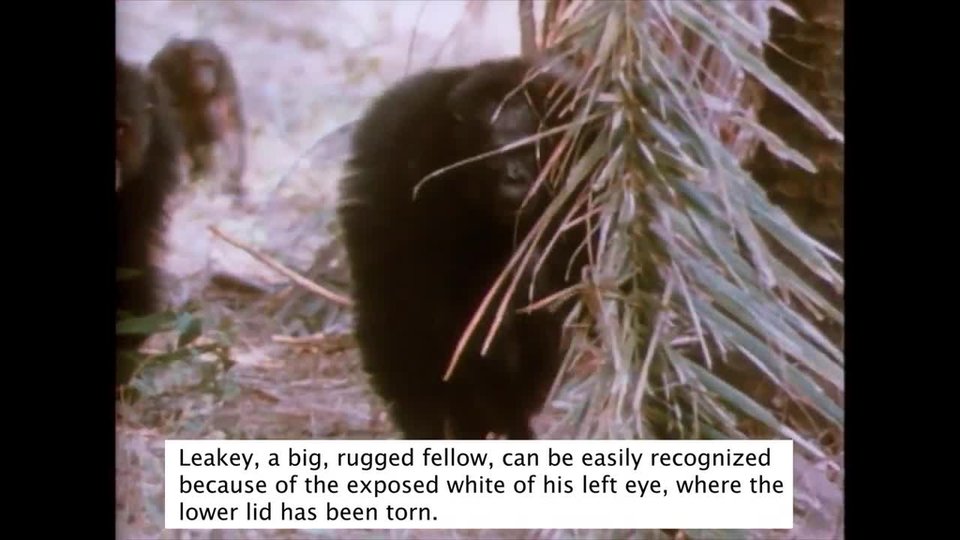

JustineAmmendoliaholdsalittle auk.

CareerChange

Ireturnedhometothinkaboutthesethings. IliveintheprovinceofNewfoundlandandLabradorineasternCanada.NewfoundlandisanislandthatisasfareastinNorthAmericaasyoucanget.The oceanandfishingplayaveryimportantculturalroleforthepeopleontheisland.But,Iknewthatourshoreswerealsopilingupwith plastic.

It’shardtosolveaproblembeforeyou fullyunderstandit.Ihadalotofquestions.Howmuchplasticwasgettingintotheoceans?Wherewasitcomingfrom?Whattypesofplasticswerethey?OnlyafterfiguringthesethingsoutcouldItacklethebiggerquestion:Howcanwestopplasticsfromgetting into oceans?

Imaybeamarinebiologist,buttotackletheplasticpollutionproblem,Ihadtobecomesomethingelse:agarbagedetective.MyresearchpartnersandIdecidedweneeded tocreateaplasticsprofileofNewfoundland’sbeaches.Wewouldaccomplishthisbyrepeatedlysurveyingsevenspecificbeaches

tostudywhatwasthereandwhereitmightbecoming from.

Greenland

Labrador

CANADA

NORTH

AMERICA

PACIFIC

OCEAN

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

Newfoundland

Collectingplastictrashfromthebeachisimportantscienceformyteam’sresearch.Butitisn’tglamorous work!

Here’sanexample:Somebeacheshavealotofplasticfoam—itcancomefromtake‑outcontainersandpackaging.Otherbeacheshavealotoffishinggear,likeropesandnets.Eachbeachis unique.

Onebeachwevisitedwaslitteredwithtrash.Amidapileofoldfood wrappers,Isawa tinyplantgrowing.Howhappyitmademetoseealivingthing,strugglingtogrowpastthemoundsoftrash.UntilIlookedalittle closer.

DetectiveWork

Everymonth,wevisitthesamebeachesandrecordwhattypesofgarbagewefind.Thisisnotexcitingwork.It’sslowandtediousandgrimy.Therecanbestrongwinds.It’softenwet.Okay,it’salmostalwayswet.Itcanevenbeabitdepressingsometimes.ButIcan’tthinkofabetterwaythanthistogetahandleonthe problem.

Whenmostpeoplethinkofplasticspollution,theythinkofwaterbottlesorplasticbags.Wecertainlydofindtrashlikethat.Wefindotherthings,too:metal,glass,rubber,cloth,evenlumber.Overtime,abeachshowsyouitspersonalitythroughthetypesandamountsofplasticthatendup there.

aplastic plant

BitsandPieces

Itturnsout,theplantIwascelebratingwasactuallyapieceofplastic!Itwasoneofthosefakeplantsthatyouputinafishtank.Iwaspretty disappointed.

Mostoftheplasticswefindare tiny.They’recalledmicroplastics.Amicroplastic isnotaspecifickindofplastic,but ratheranypieceofplasticthatisless

thanfivemillimetersinsize.Forus,thesearethehardesttoidentifysincetheyhavelosttheiroriginalshapeandleavefewcluestowheretheycome from.

Thishandfuloftrashismadeupofallsingle‑use plastic.

Yet,throughourwork,wewerebeginningtomakeconnectionsbetweenbigpiecesofgarbageandmicroplastics. Onebeach,forexample,waslitteredwiththin,plasticthreads.Atfirst,wewerereallypuzzled.Wherewerethesethingscoming from?

Thenwefigureditout:Thethreadswerecomingfromfrayedfishingropes!Sometimesropesgetfrayedandburntfromsunexposure.Whenthreadsbreakfreefromrope,theyenduponthebeachesandinthe water.