KeepItSteady

Endothermsandectothermshavevariouswaysofcontrollingtheirtemperaturetokeepfromgettingtoohotortoocold.Here’sonethatyou’llknow: sweating.

Sweatingkeepsanendotherm’sbodyfromoverheating.Here’swhathappens.First,nervessendmessagestoyourbrainthatyouareheatingup.Thebrainthensendsmessagestosweatglandsalloveryourbodytoproducesweat,whichismostlywater.Themomentsweatappearsonyourskin,heatmovesfromyourbodytothewater.Assweatevaporatesfromyourskin,youcool down.

Dogsdon'tsweat.

Instead,theypanttocool down.

HowtoBeattheHeat

Mostendothermsdon’thavesweatglands.Yet,theyhaveotherwaystocooldown.Forexample,dogspant.Witheachbreath,moistureevaporatesfromtheirtonguesandcoolstheirbodies.Birdspant,too,butnotinthesame waythatdogsdo.Birdsopentheirmouths andflutter,orvibrate,theirneckmuscles.Thisactionreleasesheatfromtheir throats.

Manyanimalsusetheirearstobeattheheat.Anelephant’slargeearshavemanyveins.Heatfromthewarmbloodflowingthroughtheveinsworksitswaythroughtheears’thinskinandintotheair.Thecooledbloodcontinuescirculatingthroughthe body.

Thiskangaroolicksitsarmtokeep cool.

Thisfennecfoxusesitsbigearstocool down.

Kangaroosdosomethingelse.WhenthehotAustralianairgetsto betoomuch,theylicktheirforearms.Astheirspitevaporates,thebloodflowingthroughtheirarmsclosetotheskincools.Alittlegross,maybe,butitworksforthe kangaroos.

Ectothermscanoverheat,too.Somelizardsburrowintothegroundtokeep cool.

Thisiguanaisn’ttryingtohibernate.

It’shidingfromthesunonahot day.

HowtoTurnUptheHeat

Whentheweatherturnscold,ectotherms,suchasreptilesandamphibians,burrowintothegroundtowaitoutthewinter.They hibernate.Sodosomeinsects,likeladybugs.Otherinsects,likemonarchbutterflies,staywarmbyflyingtowarmer climates.

Thiswalrus’slayersofblubberhelpinsulateitfromthe cold.

Endothermshaveanotherwaytoturnuptheheat:Theyshiver.Whenyouarecold,yourbrainsignalsyourmusclestovibrate.Rapidmusclemovementsgenerateheattowarmyourbody.Mammalsandbirdsshiver,butyoumaybesurprisedtolearnthatsomeectotherms,suchasbeesanddragonflies,do, too.

Endothermshavebodycoveringsthatkeepthemwarm.Hair,fur,orfeatherskeepthecoldairoutandthebodyheatin.Wolves,foxes,andmanyothermammalsgrowextrafurtoprotectagainstcoldweather.Seals,whales,andwalrusesgrowthicklayersoffatcalledblubber.Ithelpskeepthesemarinemammalswarmastheyswiminicyocean waters.

Endothermvs.Ectotherm

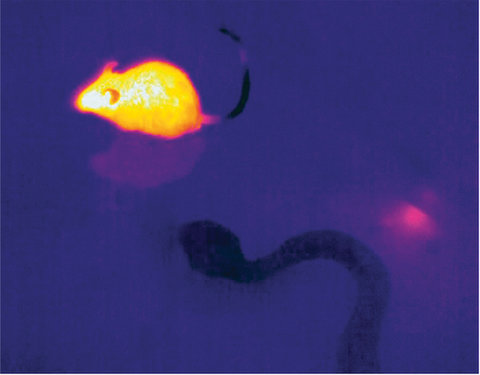

So,whichanimalshavetheadvantagetosurvival?Endothermscanmovequicklyin

acoldenvironment,whereasectotherms

canhardlymoveatall.Ifasnakewastryingtocatchamouseonacoolday,themouseprobablyhastheadvantage.However,thesnakerequiresalotlessfoodthanthemousedoes.Themousehastoeateverydayinordertomaintainahighmetabolismandbodyheat.Thesnakecouldgoforatleastaweekwithouta meal.

EndothermscanlivealmostanyplaceonEarth,fromhotdrydesertstotheicyArctic.Ectothermsareplentifulonlyinwarmandmildclimates.Theycan’tsurviveinplacesthatarecoldall year.

It’shardtosaywhichhastheupperhand.Itlookslikebothectothermsandendothermshaveuniquewaysto survive.

Amouseisanendotherm.Asnakeisan ectotherm.